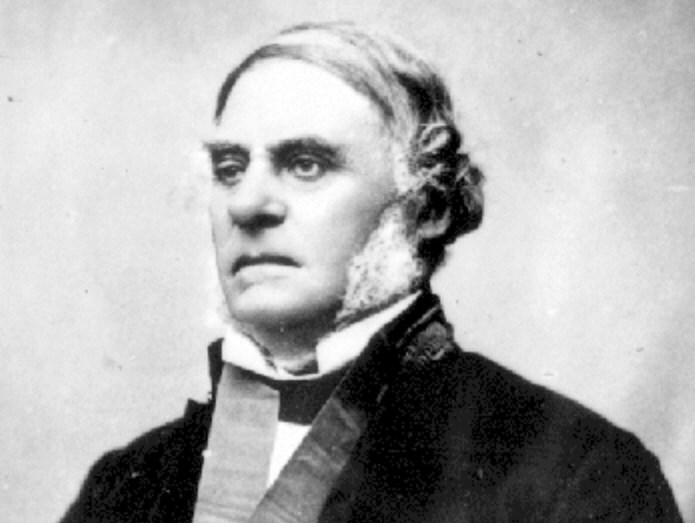

In 1803 in what was then British Guyana, James Douglas was born. His father was a Scottish merchant and his mother was what they called “free coloured” — a Creole woman of mixed African and European heritage.

Unlike his younger sister, who was as dark skinned as their mother, Douglas appeared to be Caucasian. But his later actions, including marrying a woman of Cree ancestry, have led amateur historian (and former Vancouver mayor) Sam Sullivan to believe that when Douglas built Fort Victoria, his aim was to create an inclusive society where everyone had an opportunity to thrive.

“He had a great sensitivity for black people,” says Sullivan, who has researched Douglas as part of a video series that explores the uncovered facets of British Columbian history. “It seems like he envisioned British Columbia as a place of tolerance for black and First Nations people but then the settlers came in and they had totally different ideas.”

Douglas was the chief factor of the Hudson Bay Company’s territory which in today’s terms includes British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. The territory was called Columbia and the British government had given responsibility for governing the area to the HBC.

“I call it Proto British Columbia,” Sullivan says. Its capital was Vancouver — the Vancouver in present-day Washington, that is. Our city of Vancouver is in the territory known as New Caledonia.

The Hudson Bay Company deliberately encouraged its traders and leaders to form relationships with First Nations people, Sullivan adds. “The company was in a very precarious position because it had isolated outposts all over Canada surrounded by well-armed aboriginal people who had distinctive cultures.

“The company could build a fort but it was pretty much useless if someone wanted to attack them. All they had to do was set fire to the fort. It was therefore a company strategy to inter-marry, especially with high-status native women.”

It was also good business practice. Part of the reason is that by encouraging its traders to immerse themselves in the local community, and have children, the HBC also could more easily recruit manpower for its trading routes. “Within the context of the times, the company was remarkably multi-cultural,” Sullivan says. At first the company even prohibited missionaries or European settlers “because the company thought they would be disruptive.”

Douglas was tasked with building a company outpost on the southern tip of Vancouver Island in 1841. The fort was the first building in the area, which had no white settlers yet. The fort became his home base in the spring of 1849, three yeas after the Oregon Treaty was signed.

The Oregon Treaty created the border between British North America and the United States along the 49th parallel. For the first three years, the American government didn’t have the wherewithal to send anyone to govern the area, so Douglas had retained control. But when U.S. officials arrived, the situation became untenable.

The Oregon Territory quickly posed exclusion laws that were anathema to Douglas. Neither blacks nor Hawaiians, who comprised 30 per cent of Vancouver’s population, were allowed to live there. There was even a short-lived law that said any black person who came into the territory would be lashed.

In March, 1849, Douglas packed up five wagons and headed north to Olympia, where he boarded a boat for Fort Victoria. He invited 800 black people who had experienced discrimination in San Francisco to join him in Victoria. Their descendents spread out through the Lower Mainland.

His arrival coincided with the British government’s decision to lease all of Vancouver Island to the Hudson Bay Company with the provision that it create a colony. The role of governor did not immediately fall to Douglas but he soon pushed his predecessor out, becoming governor of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1851.

History has mixed opinions on Douglas’ legacy but Sullivan believes it’s unfortunate that few people know that a man of mixed race had such an impact on the province’s history.

“Some people don’t believe that the Hudson Bay Company was a government,” says Sullivan, who now spends part of his year in Douglas’s Victoria as Liberal MLA for Vancouver-False Creek. “I think I make the case that it was. It’s a perception that needs to be corrected. I am putting this out there and waiting for a historian to correct me.”

To watch Sam Sullivan’s videos of British Columbia history go to Kumtuks.ca.