Last week, a group of young people sang songs in Yiddish at Vancouver’s annual commemoration of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. For some of the elders in the audience, including the grandparents of some of the singers, these were the lullabies of their childhood, in a language almost unheard in Vancouver or anywhere these days.

Six million Jewish people were murdered in the Holocaust, including most of the world’s Yiddish speakers. After the war, Judaism and the Yiddish language were repressed in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe.

In Israel, where a large proportion of survivors migrated, Yiddish bore the heavy history of the Jewish experience in Europe. Hebrew, which just half a century earlier had been relegated almost exclusively to religious purposes, was revived into a working language of everyday life in the new Jewish state, a symbol of renewal and determination.

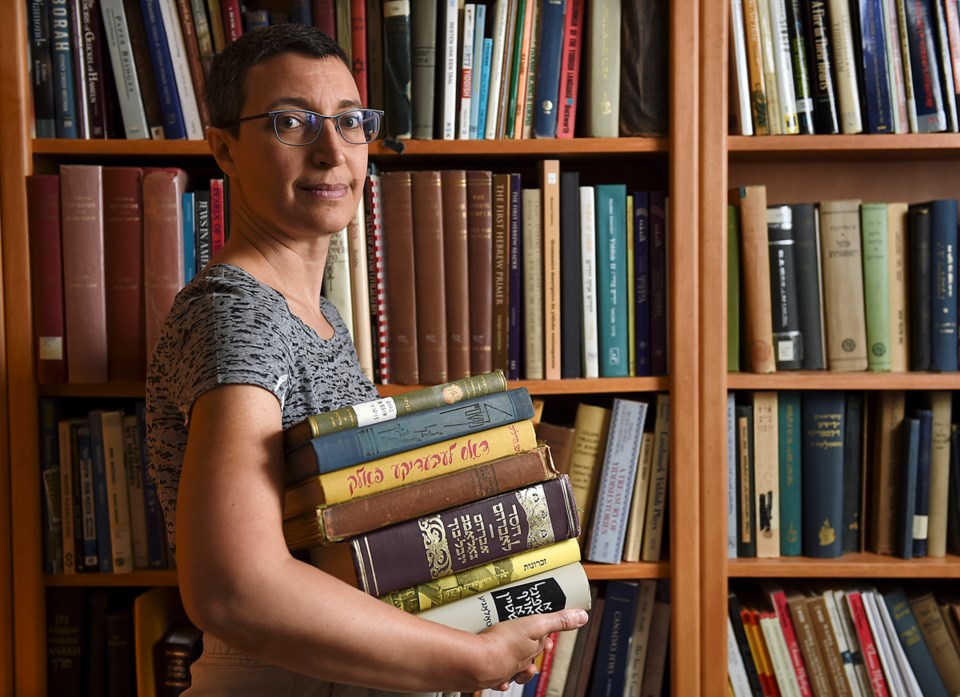

Faith Jones, a local scholar who will deliver a series of lectures on Yiddish culture at the Jewish Community Centre beginning next week, sees the language as suited to a very particular time and place.

“I think what’s interesting about Yiddish culture is it really thrived at times when the Jews were very influenced by the Western world and modernity, but were not actually integrated into the Western world and modernity,” she says. “As long as Jews were separate, there was reason for Jews to have a separate language and separate culture.”

Yiddish emerged and thrived at a time when Jews in Europe were forcibly segregated into geographic areas, prohibited from many professions and even told what to wear. This segregation meant Jews were mostly speaking to other Jews and so Yiddish developed as an insular language. However, many Jews, particularly men, were multilingual so they could communicate and interact with their Polish or Ukrainian or German neighbours. For this reason, and the fact that male scholars also knew Hebrew, says Jones, Yiddish was sometimes called a “woman’s language.”

While there were various factors, including catastrophic history, that dealt Yiddish a blow, Jones says equality and integration are also part of the equation — and that’s a good thing.

“We want to be of this world and that means that we take what goes along with that and that means that our culture changes and meshes with the rest of the world,” she says. “To me, the thing about Yiddish that makes it so interesting is that it can only exist in this moment when Jews are in between being separate and being merged.”

While Yiddish thrived as a spoken language for centuries, I was surprised to learn that Yiddish literature had a very brief heyday.

“The Enlightenment came very late to the Jews,” says Jones. “So the idea of novels and the idea of reading things for pleasure was sort of a later development.” The Jewish Enlightenment took place mostly in the 19th century, and while there was some writing in Yiddish before that, it didn’t constitute much of a literary movement.

The 1850s saw the beginning of a Yiddish literary renaissance, but a century later, the language was nearly dead.

But it is not entirely dead, Jones hastens to add, and it may have an interesting future.

There are Chasidic groups — Jewish religious communities originating from Eastern Europe but now mostly in Israel and New York — that maintain Yiddish as a lingua franca. These groups have an extraordinarily high birth rate and remain relatively insular, meaning that, like the earlier Yiddish speakers, they talk mostly to one another. There is also, on the other end of the spectrum, a movement of not particularly religious Jews keeping Yiddish language and culture alive, including here in Vancouver at the Peretz Centre for Secular Jewish Culture.

Jones thinks that the next generations of Yiddish speaking Chassidic Jews may herald the emergence of a new form of Yiddish, maybe even a new language if it strays far enough from its roots.

“I think whatever happens next, they will probably be developing either some new variety of Yiddish, some kind of mix between English and Yiddish here and between Hebrew and Yiddish in Israel.”

Traditionally, Yiddish was the language of the week, Jones says, while Hebrew was the language of the Sabbath. Even so, she adds, the first record of written Yiddish is a sign inside a German synagogue telling congregants 800 or more years ago that if they wanted to fight they should take it outside.

“There you have it,” she says. “The first known Yiddish text comes from a synagogue, although it’s definitely a secular message.”

Michael Wex, a Canadian academic and author of Born to Kvetch, has argued that Yiddish was a language that had a unique capacity to express the Jewish experience in Europe over the past millennium.

Given that history, despite her devotion to the language and culture, Jones is not heartbroken that it is in decline.

“I’m not one of these people who thinks that the decline of Yiddish is the worst thing that ever happened to the Jews,” she says. “There are a lot worse things that happen to the Jews.”

PacificSpiritPJ@gmail.com

@Pat604Johnson