In an age of instant communication, Wi-Fi connectivity to the world, and electronic entertainment in every room, it’s hard to imagine life without cellphones, gaming consoles and gadgets. This Christmas, Santa’s sack will be brimming with touchscreen cellphones, digital cameras, 3DS gaming devices, tablet computers, wireless headsets, gaming consoles like the Xbox One or PS4, and (my personal favourite for weird tech gizmos) the $300 “brain sensing headband” that measures brainwaves so you can “train your brain” to de-stress.

Flash back 70 years ago, to Christmas 1944. A time when “land lines” were more likely to be party lines, and if you weren’t home to answer your phone, you’d miss the call. The Second World War was still raging, and it was a time of shortages; the mass consumerism of modern Boxing Week sales would have been unthinkable. In an era of the icebox and coal-fired furnace, electric appliances were just starting to make inroads.

“The home of tomorrow will be an electrical home,” Westinghouse boasted in its ad for electric fridges, stoves and washing machines — the latter, an upright-drum style washer with a hand-fed wringer on top.

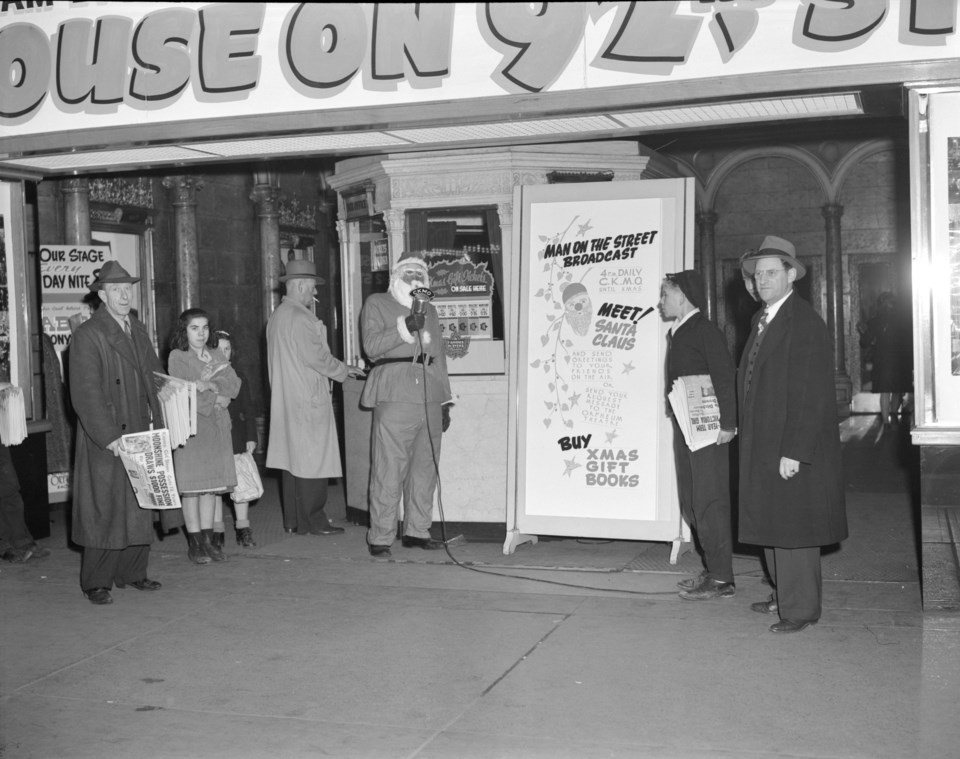

Television had been invented prior to 1944 but TV sets wouldn’t become popular for another decade. Vancouverites relied upon their radios for news of the day. A popular Christmas present “for the young lad” (in this era when girls were still expected to become homemakers, despite the influx of women into the wartime workforce) was the crystal set, a build-it-yourself radio. Selling for $3.25, it could pick up local radio stations within a 20-mile range. Headphones and an aerial were extras, at $3.85 and $1.15 respectively.

Despite winter temperatures, Vancouverites were being urged to “save one shovelful in five.” A free government booklet offered 33 tips on how to save coal, including taking delivery when the coal dealer was in the area (thus saving gasoline needed for the war effort) and accepting “whatever kind of useable fuel the dealer can supply.”

By Christmas 1954, many homes had TV sets. Television had become popular the year before, when many people purchased their first TVs to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Televisions back then were housed in wooden cabinets and required an aerial atop the set or on the rooftop. They were strictly black and white. The Admiral full console, at $259, promised “whiter whites, and blacker blacks, plus the range of in between shades.”

The Roberts Majestic Super M television (its futuristic logo featuring atoms circling a globe) featured receivers built with “Ferroxcube — the wonderful, super-magnetic material... [that] cuts out annoying interference.” The picture, the ad boasted, was “So real you can almost reach out and touch the performers on the screen!”

Popular Christmas presents for mom included electric mix masters, irons, toasters and blendettes (blenders). Or, for those wanting to splurge on a $49.50 Empire sewing machine, Pfaff Sewing Centre offered a “lay-away” plan with pick-up on Christmas Eve. Popular in the days before credit cards, a lay-away plan let shoppers pay by installment for a product they could pick up from the store once payment was complete.

For dad, popular gifts included a wrist watch (a rarity these days, when people check the time on their cellphones) or a Sunbeam Shavemaster for $17.95. Those on a tight budget could buy the electric shaver for $2 down, and $2 per month.

Families could capture the events of Christmas Day with a Kodak 8mm movie camera ($45.75) and projector ($78.50) that was “plenty big enough for living-room shows.”

Christmas 1964 saw the realization of the prediction made two decades earlier: that every home would be filled with electric gadgets.

The Broxodent electric toothbrush, at $15.75, was billed as “the most modern method of achieving better dental health.” Advertisements urged shoppers to “Reward your family with cleaner teeth and healthfully refreshed gums.”

The Broxodent had to be plugged into an electric socket; in comparison, the rival Canadian General Electric toothbrush was a cordless, rechargeable model. Ads promised it “has proved to be much more effective than hand brushing.”

An ad for Sunbeam appliances urged men to “Be the love of her busy life with time-saving Sunbeam gifts” such as an automatic mix master, waffle baker, travel hair dryer in a round hatbox-style carry case, or coffee percolator that “speed brews up to 12 cups of coffee in a few minutes.” (Espresso wouldn’t become popular until decades later.)

Another Christmas option for mom was an electric dishwasher, which Canadian General Electric calculated would save “300 hours per year of precious time” mom would otherwise spend hand-washing dishes.

For the man in your life, how about an Electrohome Titan 19-inch portable TV set for $269.50. “Please him with his own personal portable TV to tote everywhere!” (“Portable,” back then, meant a TV that could easily be picked up and moved via a handle on the top. Truly portable television viewing wouldn’t arrive on the scene until the maturation of the cellphone as a hand-held entertainment device.)

Home entertainment options ranged from the $52.88 Marconi portable record player with automatic four-speed changer that played “all types of monaural records” to the $439 Philips stereo hi-fi in a “finely crafted solid wood cabinet” that housed a turntable and speakers.

For students or secretaries, the perfect gift was a Smith-Corona electric typewriter, at $159.50. “A wonderful gift for student or careerist who depends on a good typewriter!” a Woodwards ad boasted.

Christmas, 1974 was a time when Boxing Day sales had yet to evolve into Boxing Week sales. That year, A&B Sound aimed its annual sale at the younger generation. A $199.95 package deal that included a receiver, FM stereo tuner, turntable and speakers was billed as a stereo system that anybody could afford. “When you’re young, your ears are sharp, your wallet is flat and you can hear every decibel of difference between what you can afford and what you’d like to have.”

Music, back then, came on records (either 33 RPM albums or 45 RPM singles) or cassette tape. If you wanted the latest album, you had to head on down to stores like A&B Sound or Kelly’s Stereo Marts to buy it in person; records at those stores were $3.69 and $3.78 respectively. (Music videos and MTV wouldn’t arrive on the scene until the 1980s.)

New releases to be found under the Christmas tree in 1974 included the Beach Boys’ Endless Summer, Deep Purple’s Stormbringer, The Rolling Stones’ It’s Only Rock & Roll, Stevie Wonder’s Fulfillingness’ First Finale, Elton John’s Caribou and local band Bachman Turner Overdrive’s Not Fragile.

Vancouver Sight & Sound offered JVC stereo cassette tape decks with auto reverse for $328, allowing both sides of a cassette tape to play in one sitting. Many tape decks featured the ability to record from one cassette to another, allowing people to make their own mix tapes — this, in an era long before you could assemble a library of thousands of songs on your cellphone.

Reel-to-reel tape recorders were a must-have for the serious sound recording buff. An Akai reel-to-reel, at $399, featured a four-track, two-channel stereo or monaural recording and playback system, and could be converted into a public address system.

Colour TVs were the norm by the 1970s rather than the exception (although the monster flat screens of today were a distant dream). A 14-inch Candle TV sold for $379.95, while a 17-inch Sony KV-1710 was $569.95.

By Christmas 1984, personal computers and gaming consoles were exploding onto the scene. So were video recorders that freed people from having to watch TV shows only at the time they were aired. A Panasonic VHS Video Recorder, at $449.99, featured a wireless remote that allowed viewers to “control all major functions plus change channels from your armchair” and could be set to record TV shows over a two-week period.

The first game consoles had appeared a decade earlier, but video gaming at home became a really popular pastime in the 1980s. High-tech Christmas gifts for kids included the $119.95 ColecoVision, bundled with the popular arcade game Donkey Kong, the Atari 5200 and the Intellivision.

An add-on for the latter was the $19.95 Intellivoice, a plug-in that allowed players to enjoy games that featured synthesized voices in an era when “bleep-bleep” sound effects were the norm. Electronic devices that speak to us might seem nothing special today, when we talk to Siri on our cell phones, but they were cutting edge in the 1980s, after becoming popular in the decade previously in electronic toys like the Speak & Spell.

Another peripheral, the $19.95 Atari Changer, allowed gamers to play Atari 2600 games on their ColecoVisions.

Intellivision games advertised for $9.95 that Christmas included Space Battle, Space Armada, Bump ‘n Jump, Star Strike, Sharp Shot, Astrosmash, Frog Bog, Vectron, and Maze-a-tron —all obscure titles today.

By the 1980s, cordless phones and answering machines were the norm, as was the microwave oven, the video camera and the Sony Walkman, which allowed music buffs to listen to their favourite album on cassette tape as they jogged. Personal computers, however, were just starting to become a hot Christmas gift.

An IBM PC Jr. with 128 KB of memory and two disk drives for 5 1/8-inch “floppies” sold for $1,469 at Future Shop. A colour monitor with 13-inch screen that “displays text and graphics in as many as 16 vivid colors” was extra, and sold for $634.99.

At the low end, the Commodore 64, billed as “the world’s best-selling name computer on the market today” was just $284.99.

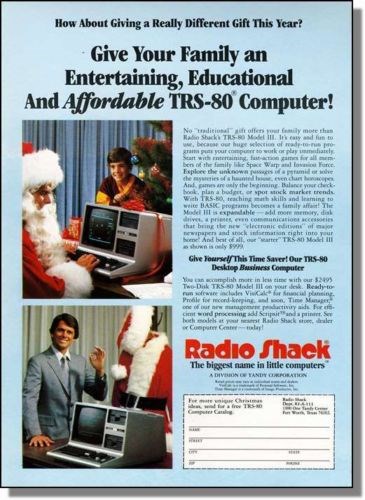

The Apple Macintosh, with its graphical user interface and mouse, had been released earlier in 1984, but most computer buffs still interfaced with their computers via the typed-in commands of DOS. Apple had yet to become the household word it is today. This was the year I bought my first computer; I remember being puzzled by the icons on the Macintosh’s screen. I opted for the TRS-80 personal computer instead — a mistake, in hindsight.

“Every computer system needs a printer!” one 1984 ad noted. Back then, printers were either dot matrix or daisy wheel, required special perforated, tractor-feed paper, and cost $399.99 to $599.99

Christmas of 1994 marked the dawning of an era of connectivity. A Motorola flip-phone (a device that was the stuff of science fiction shows like Star Trek just three decades earlier) sold for $99.

Cellphones, however, were still being given a run for their money by pagers — which at $9.95 per month had service plans that were a fraction of the $49.95 per month cellphone plans cost.

Other must-have electronics for under the tree included the Sharp electronic organizer, a flip-open electronic device about the size of a daytimer — which was what it was meant to replace. First prototyped in 1986, the electronic organizer became popular in the 1990s, at a time when cellphones didn’t have the functionality they do today.

The lower-end organizer packed “eight major functions” into a single device: telephone directory, expense tracking, calendar, schedule, memo, anniversary, clock and calendar, for just $39.99. The more expensive model, at $124, featured a 128 KB memory and could display four lines of text that were 20 characters wide.

Today, we look back at many of the “high tech” gadgets and devices of previous decades and shake our heads at how primitive many of them seem. Likewise, modern virtual reality gaming consoles like the Omni and 3-D printers — cutting-edge technologies today — may seem laughably primitive to our grandchildren.

The past 70 years has seen technology evolve from vacuum-tube radios to touch screen cellphones that pack the functionality of a roomful of electronic devices of decades gone by.

Seventy years hence, in Christmas 2084, what science-fictional wonders will we find under the tree?