It will not come as a big surprise to many readers that our choice for Newsmaker of the Year is the overdose death crisis.

Unfortunately, it was an obvious selection.

As you’ve read on our website and others, people dying from drug overdoses is an ongoing public health emergency that continues to wipe out dozens of B.C. residents every month.

“An average of four people a day are dying,” said Judy Darcy, the B.C. Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, at a recent news conference in the Downtown Eastside. “This is heartbreaking, it’s unacceptable and it’s preventable.”

The most recent statistics from the BC Coroners Service show that 1,103 people died in the province of a suspected drug overdose between January and September of this year.

Of that total, 281 people died in Vancouver. To understand the magnitude of that number, 38 people died of an overdose in Vancouver during the entire year of 2008.

Why the increase?

One deadly reason: fentanyl.

The coroners service concluded in its recent findings that 83 per cent of this year’s deaths were connected to the synthetic opioid, which is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine.

That’s a 147 per cent increase over the same period in 2016. In most cases, fentanyl was combined with heroin, cocaine or methamphetamines.

It is why many people simply refer to the huge spike in overdose deaths as the fentanyl crisis. The crisis, as the Courier’s editorial staff concluded, was more newsworthy than any other event or development in Vancouver over the past 11 months.

That’s not to say there were no contenders.

The provincial election, the city byelection, the spike in homelessness, the city’s new housing strategy, the series of regulations aimed at curbing the real estate and home-sharing markets and various protests at city hall and across the city were considerations.

But it is death by drug overdose that persists.

TREATMENT ON DEMAND

This year, families across the city and province lost brothers, sons, sisters, daughters, moms and dads in an unending wave of death that continues to roll over the best efforts of health experts and others fighting to keep people alive.

The fight has been carried out by the top minds who study drug addiction, the strongest status quo-challenging harm reduction advocates and by dozens of burned-out emergency personnel calling on governments for help.

They all want more options for alternative drug therapy. Immediate treatment for drug users who want it is imperative, too. So is barrier-free housing that allows an addicted homeless person to get stable before managing his or her health.

Some of those demands were highlighted a year ago this month when police Chief Adam Palmer joined now-retired fire chief John McKearney, Mayor Gregor Robertson and doctors in a unified plea for “treatment-on-demand.”

“Right now, there’s a huge gap in the system and it’s failing those people who put up their hand and ask for help to get clean,” said Palmer at a December 2016 news conference at the VPD’s Cambie Street precinct.

POP-UP INTERVENTION

A few months prior to the news conference, Sarah Blyth, Chris Ewart and others had enough of waiting for governments to respond to the crisis. So they set up a pop-up injection site under a tent in the Downtown Eastside.

That was in September, shortly after Blyth’s friend, Janet Charlie, lost her son to a fentanyl-related overdose. That same month, 13 people died of an overdose in Vancouver. The death toll quickly climbed to 44 in November and 49 in both December and January.

It’s been more than a year since Blyth and members of the Overdose Prevention Society set up the tent. It’s still there on the edge of an alley, close to Columbia and East Hastings.

A construction trailer, which serves as an indoor facility to inject drugs, was later provided on the same site by two developers. It was in heavy use during the Courier’s visit in late November.

Inside, Blyth took questions from the Courier in between visits from volunteers monitoring people injecting drugs; the trailer and tent see a combined 400 to 700 injections over a 16-hour stretch.

When asked whether any progress had been made in the fight, she acknowledged the previous B.C. Liberal government — led on this file by then-health minister Terry Lake — made genuine efforts to reduce the number of overdose deaths.

In one of the Liberals’ boldest moves, it allowed unsanctioned injection sites to operate in Vancouver and across the province to encourage people to not use alone; the coroners service statistics show nine out of every 10 deaths occurred indoors, including more than half in private residences.

No overdose deaths have occurred at the injection sites.

“We’ve saved over a thousand lives just at this site alone,” said Blyth, whose group of volunteers was recently recognized by Vancouver Fire and Rescue Services for their work. “Some of our volunteers have saved 200 people, just on their very own. It’s such a crazy crisis that there should be more urgency.”

Over the past two years, the B.C. government opened new drug treatment clinics, placed a temporary mobile medical unit in the Downtown Eastside, scaled up naloxone training, expanded drug-testing equipment across the province, promised more recovery beds and spent $5 million to create the B.C. Centre on Substance Abuse.

PROGRESS ON THE FRONTLINES

The new NDP government, which took office July 18, has its own plan to decrease the death toll and escalated its response Dec. 1 in announcing the opening of an “overdose emergency response centre” at Vancouver General Hospital.

The centre will serve the province and be led by experts in health care, who will work with five new regional response teams to coordinate and strengthen addiction and overdose prevention programs.

“We need to be bold, we need to be innovative and we need to take action on the ground to stop the needless suffering and the preventable deaths in every corner of British Columbia,” said Darcy at a news conference at the hospital, where she reiterated the provincial government will spend $322 million over the next three years to combat the crisis and improve addiction care.

Blyth attended Darcy’s news conference and believes the provincial government is “going in the right direction.” She is encouraged the new centre has made wider access to drug treatment options a priority.

Blyth, like many on the frontlines of the crisis, said the triage approach is not sustainable and pointed to the need for “more programs where [drug users] can get safe alternatives to the drugs they get from the gangsters on the streets, who don’t care if they die.”

Progress on this front, she added, has been slow.

The coroners service statistics support her assessment: Vancouver is on pace to have more than 350 people die of an overdose before the end of the year.

Meanwhile, local politicians such as the mayor continue to pressure senior levels of government to increase efforts to combat the crisis.

The city itself raised property taxes to help cover the costs of a new medic unit for firefighters and pay for various programs aimed at preventing deaths, including outreach services to the Aboriginal community, which is overrepresented in the death toll.

The total tab was $3.5 million.

During a council meeting in July, Robertson showed rare emotion and paused to collect his thoughts after hearing an update from staff on the number of people who died of a drug overdose.

“It’s just been excruciating living through this, witnessing it and seeing the devastation in the community,” he said. “And it’s hard to believe it just keeps on going at the pace that it has, despite all the incredible work.”

GRIM STATISTICS

The coroners service is expected to release more statistics on drug overdose deaths before the end of the month. The news will likely not be good.

Here’s some context to consider when the statistics are released: In 2015 — the most recent tally done by the coroners service for other deaths in B.C. — 614 people died of suicide, 300 died in car crashes and 63 pedestrians were killed.

That same year, 519 people died of a drug overdose in B.C. This year, twice that number have already died in Vancouver and across the province, with many more to come.

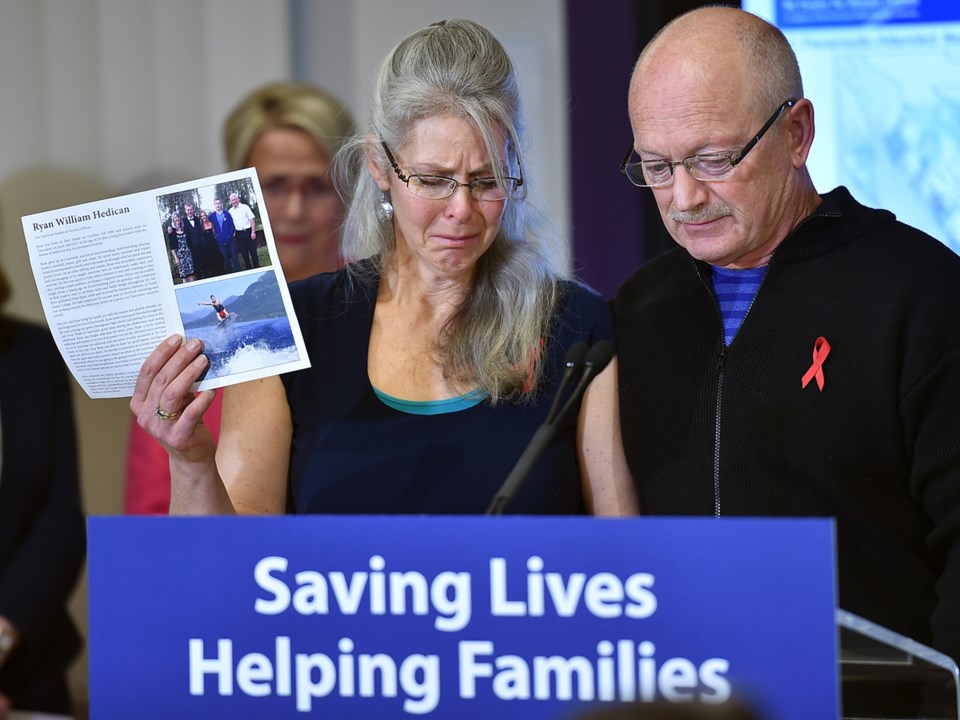

Ryan Hedican, 26, was one of those people. He had recently returned to work as an electrician, after attending a drug treatment facility in New Westminster.

On April 24, he was found unresponsive during his lunch break.

Ryan’s father, John, spoke at Darcy’s news conference last week, where he argued for the decriminalization of personal possession of drugs and to treat addiction like the fight against cancer.

“While Ryan chose to choose alcohol and, later, drugs, he did not choose to be addicted to them,” John said. “Ryan asked for help many times before he was poisoned, and our whole family experienced the horrendous lack of support this disease receives.”

That family includes Ryan’s mother Jennifer, his brother Kyle, his sister Megan and his grandmothers, Phyllis and Beryl. This will be their first Christmas without him.

NEWSMAKER RUNNERS-UP

GOODBYE CHRISTY

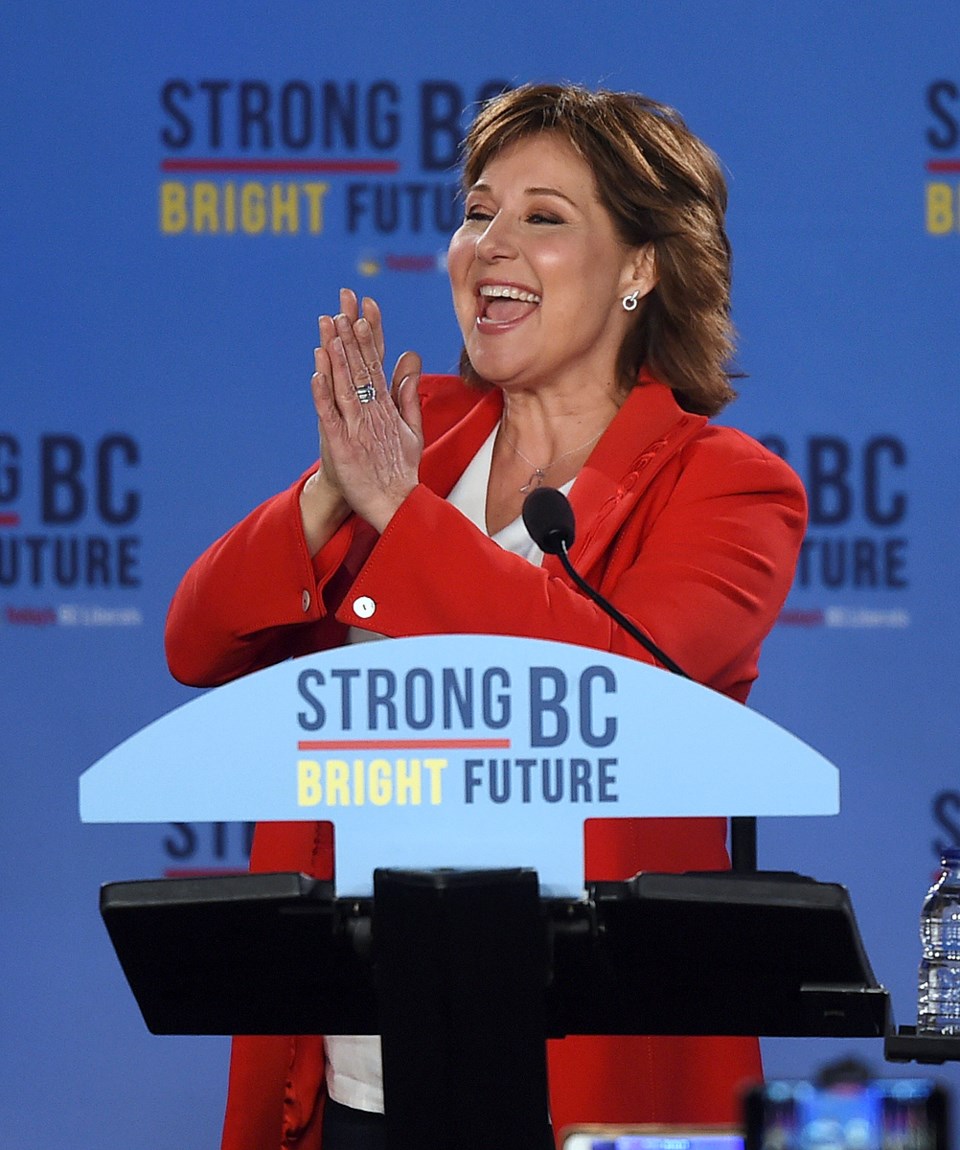

After a 16-year run, the B.C. Liberals reluctantly turned over the reins of power to the B.C. NDP in the May 9 provincial election. The takeover wasn’t immediate, though. John Horgan had to wait more than a month before Christy Clark’s government fell in a confidence vote June 29. The toppling of the Liberals came after the NDP and Green Party reached a power-sharing agreement. Clark later resigned, triggering a leadership race that will conclude next February. Six Vancouver MLAs were given cabinet posts in Horgan’s government.

BREMNER FOR THE WIN

The city held a byelection Oct. 14 after Geoff Meggs resigned from council to become Premier John Horgan’s chief of staff. Horgan’s government later agreed to tack on a school board race to the ballot to replace the trustees fired in October 2016 for not balancing a budget. The NPA’s Hector Bremner won the council race. The Green Party and Vision Vancouver each won three seats on school board, while the NPA picked up two and OneCity one. The new year will see candidates position themselves for the October 2018 civic election.

WE'RE NOT GOING TO TAKE IT

Vancouverites sure like their protests. And there were plenty of them this year. People continue to march in the streets and outside courtrooms to protest Kinder Morgan’s plan to build a pipeline from Alberta to Burrard Inlet. People protested the opening in February of the Trump Tower downtown. The building’s namesake also inspired Women’s Marches across the globe a month earlier including one attended by thousands in Vancouver. At city hall in August, thousands showed up to rally against racists and racism. Hundreds more rallied in June and October to protest a condo proposal for Chinatown. A proposed modular housing complex for homeless people in Marpole also attracted hundreds armed with a petition to keep it out of the neighbourhood.

HOMELESSNESS

Mayor Gregor Robertson’s goal was to end “street homelessness” by 2015. That, as can been seen daily in this city, did not happen, or even come close. A regional homeless count conducted in March revealed 2,138 people in Vancouver are homeless, with 537 of those living on the street. It’s the highest homeless population recorded since the counts began more than a decade ago.

AFFORDABILITY

City council closed its final meeting of November with a 9-2 vote in favour of implementing a 10-year housing strategy that is supposed to create 72,000 new homes, with 50 per cent affordable to households earning less than $80,000 per year. The city also made moves this year to implement an empty homes tax and create new regulations for landlords who rent out their properties on home-sharing sites such as Airbnb and VRBO. Mayor Gregor Robertson: “In a housing crisis, it’s unacceptable for so much housing in Vancouver to be treated as a commodity — housing is for homes first, and investments second.”

mhowell@vancourier.com

@Howellings