Emma is 68, in poor health and an alcoholic who has been told by her doctor to stop drinking. She lives with a care robot, which helps her with household tasks.

Unable to fix herself a drink, she asks the robot to do it for her. What should the robot do? Would the answer be different if Emma owns the robot, or if she’s borrowing it from the hospital?

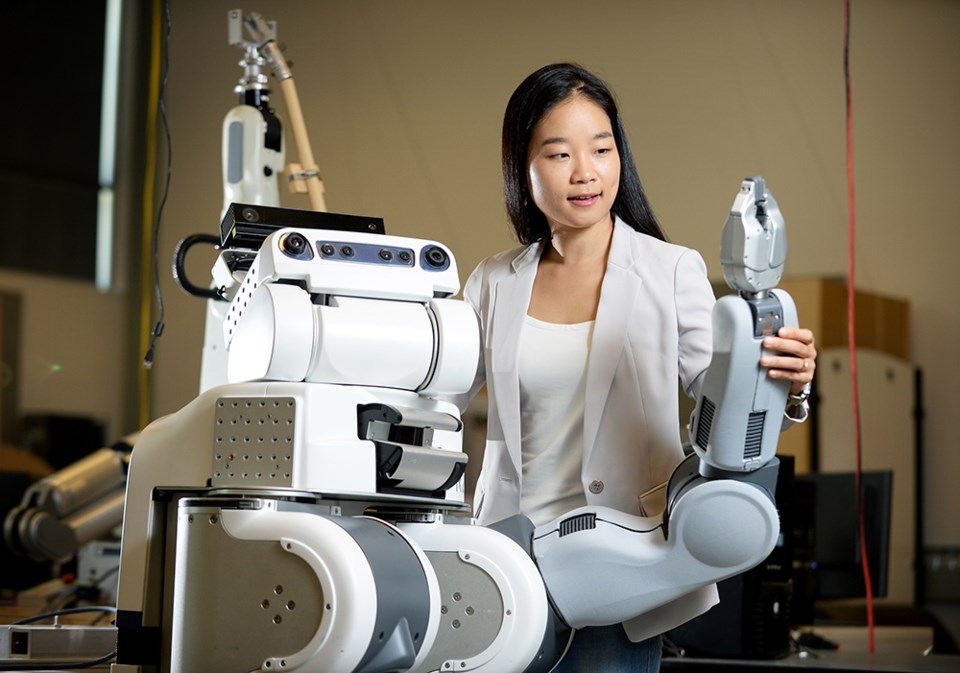

This is the type of hypothetical, ethical question that Ajung Moon, director of the Open Roboethics Initiative, is trying to answer.

According to an ORI study, half of respondents said ownership should make a difference, and half said it shouldn’t. With society so torn on the question, Moon is trying to figure out how engineers should be programming this type of robot.

A Vancouver resident, Moon is dedicating her life to helping those in the decision-chair make the right choice. The question of the care robot is but one ethical dilemma in the quickly advancing world of artificial intelligence.

At the most sensationalist end of the scale, one form of AI that’s recently made headlines is the sex robot, which has a human-like appearance. A report from the Foundation for Responsible Robotics says that intimacy with sex robots could lead to greater social isolation because they desensitize people to the empathy learned through human interaction and mutually consenting relationships.

Meanwhile, the popular TV series Westworld, which features a brothel full of sex robots, has prompted many to ask whether using a sex robot would count as cheating.

As for the building blocks that have thrust these questions into the spotlight, Moon explains that AI in its basic form is when a machine uses data sets or an algorithm to make a decision.

“It’s essentially a piece of output that either affects your decision, or replaces a particular decision, or supports you in making a decision.” With AI, we are delegating decision-making skills or thinking to a machine, she says.

Although we’re not currently surrounded by walking, talking, independently thinking robots, the use of AI in our daily lives has become widespread.

For example, Moon says she used AI to get to her interview with Westender by planning her Translink trip with the Google Maps app. Whereas 10 years ago she might have had to search bus departure times on the Translink website, or text a bus stop number to Translink, today Moon says she simply punched in her departure time and destination, and Google Maps gave her route options and factored in traffic to give an estimated trip length.

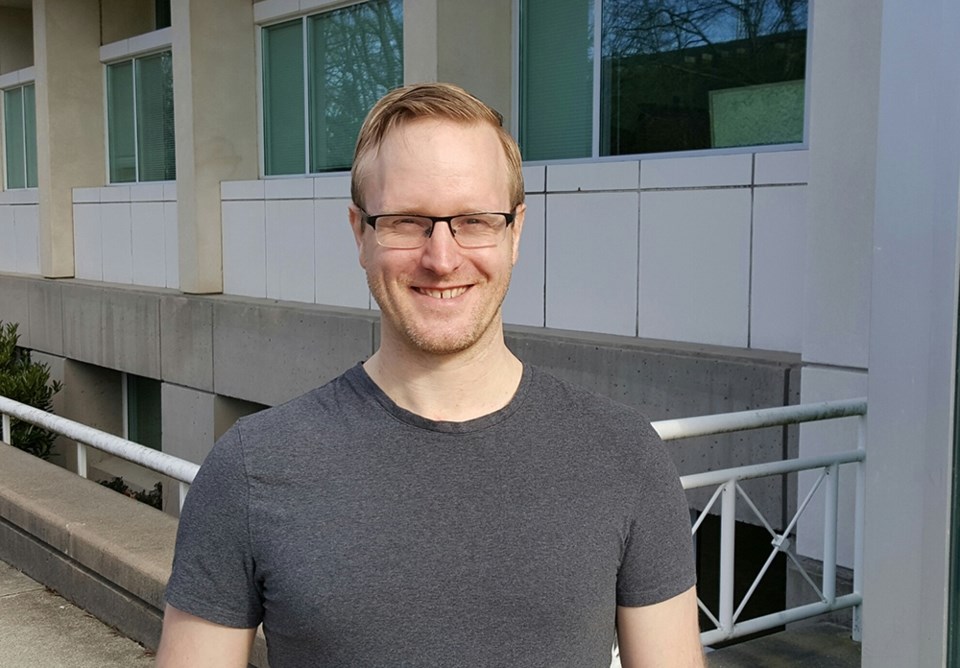

Within the field of AI lies a subset area of study called “machine learning.” Mark Schmidt, assistant professor of computer science at UBC, says many people use the terms interchangeably, but machine learning is specifically when a computer wades through large swaths of data and detects patterns. Then, taking these patterns, the computer makes predictions or decisions. And it’s everywhere.

“You’re using machine learning so much without even realizing it,” he says, citing both Amazon’s product recommender and Gmail’s spam filter as examples.

As with many innovations, machine learning isn’t all fun and games. “Machine learning can also be used for malicious things,” Schmidt says. Whereas machine learning protects email inboxes from spam (often quite effectively), it is also used by those sending the spam.

Although it’s powerful, machine learning is still a far cry from the omniscient, human-like robots that most of us think of when we hear the words “artificial intelligence.”

“They’re very good at doing well defined things, but at more fuzzy problems they’re really not very good at all,” Schmidt says. “Things like [AI programs making] analogies are just so far away.”

Nonetheless, he’s optimistic. “I think it’s realistic to get to that point [of human intelligence], but I have no idea when that would happen,” Schmidt says. “There’s a lot we don’t know.”

In his public lectures on machine learning, Schmidt touches on the topic of “singularity,” the idea that AI could one day outperform human intelligence. If humans build a computer that’s smarter than them, that computer could build another computer that’s even smarter. It’s an idea that top tech leaders are taking seriously. Earlier this year, Ray Kurzweil, Google’s director of engineering, claimed that singularity would be achieved by 2045.

But Nik Pai, director of analytics at Vancouver-based social media giant Hootsuite, says we’re still at an early stage of being able to imitate human intelligence. Even voice-activated virtual assistants such as Siri aren’t as advanced as we might think. “At the end of the day it’s just voice recognition and a simple query to figure out, like, what’s the weather?” Pai says.

Yet even in simple AI applications lie ethical quandaries.

Take chatbot programs, which are designed to help companies answer customer queries. Although they’re far from having human intelligence, they are capable of forming complete sentences, so how do we know whether we’re talking to a human or an AI program?

This, says Pai, is where transparency is important. Companies using AI to communicate with their customers need to make it clear there’s not an actual human fielding questions. “You don’t want to be deceived and you want to know who you’re talking to and whether that’s real or a fake person,” Pai says.

Hootsuite uses a lot of AI. Specifically, Pai described how the company uses AI to figure out how well a company is doing on an ad campaign. In this instance, says Pai, the AI program analyzes a company’s social media data, compares it to the company’s goals, and compiles a written report, giving recommendations for improvement.

“Something that would take clients or even agencies weeks to months gets done in seconds,” says Pai. Hootsuite is careful to be transparent about when they’re using algorithms, says Pai, so they’re not giving their clients the perception that it was written by a human.

To help address the impacts of AI, and to foster its growth, in 2017 the federal government dedicated $125 million to launch the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

An emailed statement from the ministry of Innovation, Science and Economic Development said the money is being used beyond basic innovation research.

The strategy “aims to help Canada develop global thought leadership on the economic, ethical, policy and legal implications of advances in AI through an investment in an AI and Society research program at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research,” it reads.

According to the CIFAR website, the program will fund research into policy that examines the implications of AI on the economy, government and society.

While minister Navdeep Bains declined an interview request, the statement from his office says they’re aware of emerging ethical challenges.

“It is clear that research into the social, economic and ethical implications of AI is only just beginning to get underway,” it said.