* Ed. note: The following story was originally published in the Jan. 17, 2007 edition of the Courier.

"A tree falls in Stanley Park. One tree. Trees are falling all over North America in a storm. But there is no fallen tree we venture to say, which caused more aggravation, more wasted time, more fury, than the one tree, which fell on a car in Stanley Park on the afternoon of Oct. 11, 1962. The traffic tie-up reached to Granville Street, in double and triple lines. Nobody could lift the tree because men with axes and saws could not reach the car for traffic. Motorists were advised to turn around and use Second Narrows Bridge. For an hour, there was another big hold-up in Stanley Park..."

The above incident, reported in the Province of the day, was the first hint that a hurricane was coming to Vancouver that fall week. And as that same newspaper reported, by the time the hurricane, which became known as Frieda, had ravaged the city and Stanley Park over two days, it had become the worst storm in the city's history until that moment.

It's also a great example of the adage that history repeats itself. The storms, thousands of downed trees, power failures, smashed cars and houses, traffic snarls and injuries Vancouverites have experienced in the past month would be intimately familiar to their predecessors in 1962. Just as today, people were aghast at the scale of damage to Stanley Park in the aftermath, and rushed to offer ideas to deal with the downed wood or to help with the cleanup.

But there was one major difference between the recent storms and the winds that swept the city in 1962.

We had a few days warning about what to expect. It turns out the Oct. 11 incident described in the Province report was the buildup to a windstorm that hit the unprepared city that day and the next, bringing winds of 126 kilometres an hour. And in 1962, no one saw it coming.

If anyone experienced the brunt of the storm, it was Stuart Lefeaux, who worked for the parks board for 34 years and was superintendent when Frieda came ashore.

Sitting in the sunny living room of his Arbutus home, a tall distinguished-looking Lefeaux, who retired in 1979, remembers he and his family were living in caretaker's residence in the park near Lost Lagoon that October. He recalls the moment when he realized this was a storm to rival no others in his memory.

"My wife and I were visiting friends in the British Properties [in West Vancouver] for dinner," says Lefeaux, who for 27 years lived beside Lost Lagoon where the Pooh Corner Daycare is now situated. "From there we could see the entire city. Trees were coming down on the transformers and we could see the flashes as they exploded. That was my first intimation anything was wrong."

Lefeaux and his wife hurriedly left the dinner party and rushed to get home where their two children were in the care of a babysitter. The drive took longer than expected because the Lions Gate Bridge was already closed to traffic and the couple was rerouted to the Second Narrows Bridge.

"Driving into the city was unbelievable," says Lefeaux. "Signs were blowing everywhere, billboards were strewn about and trees were falling down. The wind was howling at close to 100 kilometres per hour. It took us a long time to get home."

The couple eventually made it home and road out the storm with their children. Lefeaux says the city had no warning Hurricane Frieda was heading its way [WHY?] and the force of the winds caught everyone by surprise.

"That was 44 years ago, but I still remember Hurricane Frieda. Some people called the storm a typhoon but Hurricane Frieda seemed to stick," says Lefeaux. "It was the first big storm on record to hit the city and I had never seen anything like it in all my time with the park board."

According to a history of the storm written by parks board communications coordinator Terry Clark, both "hurricane" and "typhoon" can be considered "a little right and a little wrong" when describing Frieda.

The term hurricane refers to severe Atlantic weather systems and those in the Eastern Pacific. The term typhoon is the designation of Pacific storms west of the International Date Line. Frieda had the distinction of starting as a typhoon and moving east instead of west, which is the usual pattern for typhoons, and becoming a hurricane while merging with another tropical storm. According to Clark, weather professionals like to call Frieda an "extropical" storm.

Dave Jones, a meteorologist with Environment Canada, notes that until recently the great winds of Frieda were the second highest on record. Until last's month infamous storm, the highest winds recorded in our area blew through the airport on Nov. 25, 1955, at 129 km/h.

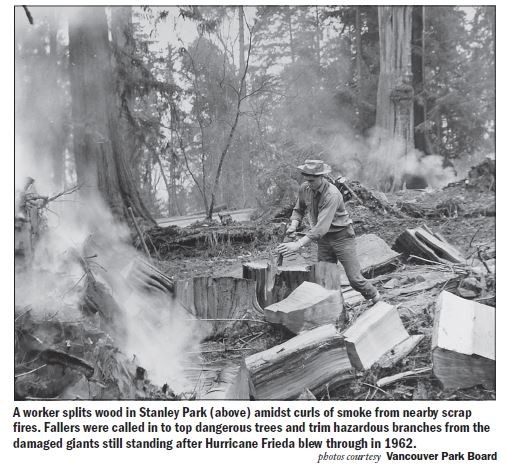

The day after the storm Lefeaux headed out to survey the damage to Stanley Park. He was devastated at the sight of the thousands of trees blown down. A photograph from the time shows a tiny Prospect Point Cafe with a large tree crushing its roof. A much larger Prospect Point Cafe was also heavily damaged in last month's storm. Just like today the total estimate of trees lost in Stanley Park in 1962 was 3,000, with many more blown down across the city. Lefeaux says that just as the recovery is being undertaken today, in 1962 clearing roads throughout the park became a priority.

He adds it's ironic the recent storm arrived just weeks after a decision was made to allow the Vancouver Aquarium to expand, which means the removal of about 30 trees.

"People were so upset about those trees and now we've lost 3,000," he says.

Several areas near Prospect Point were the most heavily damaged by the 1962 storm, just as they were last month. But Lefeaux says the storm damage wasn't all bad news.

"The storm opened up quite a swath behind the Hollow Tree and we made that into a picnic area," he says. "The biggest result though was that we were able to build the children's zoo and miniature railway in an area cleared by the blow down."

The storm also cleared the way for the development of the Prospect Point picnic area and created viewpoints and vistas towards the ocean and North Shore.

"In a way it was a good thing," says Lefeaux. "And maybe now they'll get two or three new picnic areas."

Just like today, the parks board in 1962 was inundated with ideas from the public on what to do with the logs left over from the storm and for the use of areas that will eventually be cleared as the cleanup of Stanley Park continued. Ideas presented to today's board include cutting cedar logs into three-inch chips branded with the date of the 2006 storm and selling them in gift shops and allowing First Nations groups to carve totem poles from downed logs. Building a heritage-style horse barn out of the logs in an area cleared by the blow down is another idea being offered to the board that would not have been out of place 44 years ago.

"People had ideas," says Lefeaux, laughing at the memory. "But common sense prevailed."

Lefeaux has his own idea of what he'd like to see happen in the aftermath of the most recent storm. He adds for the first time in a long time Beaver Lake is visible from Pipeline Road.

"I'd like to see that cleared out and remain visible from the road," he says.

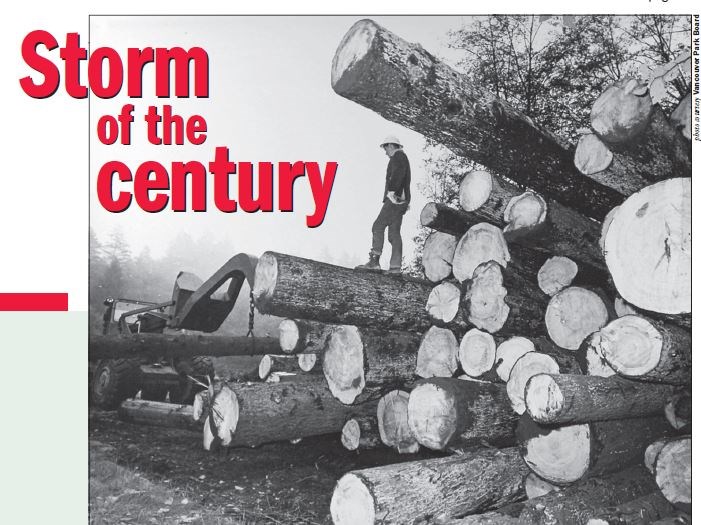

The board back then voted to log and sell the wood and loggers stacked up downed trees in various areas around the park for potential buyers to view. Lefeaux notes that just like today, Hemlock trees dominated the piles, which at the time sold for very little.

"We maybe made $3,000 or $4,000 from the sale," he says. "A lot of it was broken, was the wrong length or the wrong species. It was not first-class lumber, though there was a few nice cedar to fight over."

Lefeaux says logging Stanley Park was much simpler in 1962 than it would be today partly because much of the seawall hadn't been completed. Park trails were converted back to skid trails, and some of the wood was hauled out and pushed into the ocean, where barges collected it. Such an operation could not be conducted today because of the seawall. The board of the day also decided leaving the downed trees to nature was not an option because they could potentially create a fire hazard.

Just as we've seen in recent days, the trees of Stanley Park were big news following Hurricane Frieda. But while the 2007 coverage has focused on the fate of the downed wood and the future of the park's forest, the 1962 stories zeroed in on the horror caused by massive trees falling on roads and buildings. One headline from The Province, dated Oct. 13, 1962, reads "Terror among giant trees."

"Stanley Park Causeway became a scene of terror and death Friday midnight as the violent winds flung giant fir trees across the road," the article reads. "Six cars were smashed by the toppling trees and firemen with chainsaws tried to clear the road and extricate the injured. Two buses and 42 cars were blocked while their panic stricken passengers huddles near their vehicles and gazed up in terror at the swaying trees...During a particular violent blow, while trees waved like matchsticks, a policeman ordered everyone to get back into the buses and lay on the floor..." Other headlines of the day include "Storm-jolted mainland mops up, counts 7 dead, loss in millions," "Many still in darkness," "City Contingency Fund drained," "Storm leaves trail of death and devastation" and "Damaged shops hit by looters."

One Province news story tells the tale of Stanley Park, calling it the hardest hit area of the city. Besides blowing down forest trees the wind knocked over a 10-foot high concrete wall at the tennis courts, as well as a 50-foot ornamental blue spruce near the Georgia Street entrance to the park, which was traditionally decorated with Christmas lights each year. Hundreds of trees along city boulevards were also toppled and 60 parks board employees spent the following weekend sawing them to make way for traffic.

Lefeaux is quoted in the news story saying damage to city parks and boulevards would run into hundreds of thousands of dollars.

"Where there is a clearing, the wind has cleared a little more, rooting out hundreds of trees," Lefeaux told the Province at the time.

But as devastating as Hurricane Frieda was, Lefeaux estimates the damage from the Dec. 15 storm was "three times as bad." In 1962 the damage in Stanley Park was estimated at $150,000. While the 2007 parks board can't put a dollar figure to the cleanup costs from recent storms, it's estimated to be in the millions. So far the provincial government has dedicated $2 million to help restore the park, while the public has donated $2.6 million.

"The totality was not as great with Hurricane Frieda," he says.

Lefeaux blames part of Stanley Park's vulnerability to storms to the heavy logging that hit the area in the 1880s. While fir and cedar trees were much coveted by loggers, hemlock trees were not. But hemlock trees create problems during high winds because while they grow to amazing heights, in comparison their roots are extremely short. In high winds the trees are the first to topple, taking down everything in their path.

"And once an area is logged the first trees to grow back are hemlock," says Lefeaux. "Unfortunately it's also the weakest and first to go down."

Cleanup in 1962 was also likely easier. Vancouver 44 years ago had a high unemployment rate, which meant an abundance of both skilled and unskilled workers at the ready to help restore the park. Employees were hired through a federally funded program called Winter Works.

"The problem is today there's no workers to do the job," he says. "It was a huge job, but it was a nice job working to restore the park, just like it will be today."

And one of the biggest differences between the December storm and Frieda has been the TV coverage.

"People can really see the damage," Lefeaux says. "I'm glad the public is helping raise so much money. The end result is that Stanley Park will be much more interesting than before."