The B.C. government opened an “overdose emergency response centre” Friday at Vancouver General Hospital to significantly scale up its effort to reduce the number of people who continue to die of a drug overdose.

The centre is located in a classroom-sized room and led by experts from health, law enforcement, the First Nations community and others who will work closely with five new regional response teams to coordinate and strengthen addiction and overdose prevention programs across the province.

“We will be driven by data, we will focus on a community by community basis to implement strategies we know can prevent overdose deaths,” said Dr. Patricia Daly, the chief medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health, who will serve as the centre’s executive director. “We will address any gaps, we will remove barriers, work with our colleagues in regions around the province, who will in turn work with their local first responders and community partners.”

The centre will focus on providing wider access to substitution drug treatment options, opening more injection sites, ensuring better screening of patients at hospitals for drug use, conducting clinical follow-ups for people at risk of addiction and overdose and increasing the availability of naloxone.

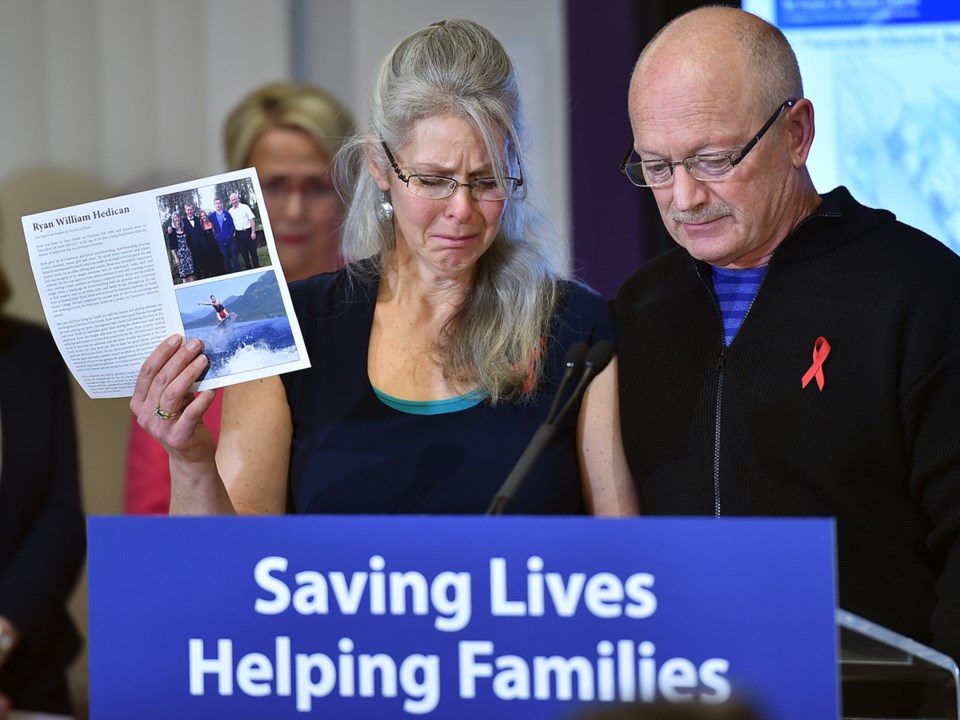

Daly outlined the centre’s work at a news conference at the hospital, where John and Jennifer Hedican told reporters about the overdose death of their 26-year-old son, Ryan. John described his son’s death, which occurred April 24, as “a fentanyl poisoning.”

“He was found unresponsive at his work site during his lunch break,” said John, noting his son spent the previous eight months at The Last Door recovery facility in New Westminster before returning to work as an electrician. “While Ryan chose to try alcohol and, later, drugs, he did not choose to be addicted to them. Ryan asked for help many times before he was poisoned, and our whole family experienced the horrendous lack of support this disease receives.”

He said Ryan needed immediate help but didn’t get it from a hospital or family physician. The Hedicans also spent thousands of dollars to cover costs at two treatment centres. He said Ryan wrote a letter while at The Last Door that he was supposed to read once he was one-year clean.

His parents read it Sept. 15, the anniversary date.

“Ryan wrote of how he wanted the strong bond back with his family, to be back at work as an electrician, to listen to music, read books, play sports and have a relationship again,” John said. “Addiction took all those things away Ryan wanted in life.”

Daly pointed out that most people who died of a drug overdose had previously visited a hospital emergency department or a health care provider in the year prior to their deaths. She said the visit wasn’t always related to an overdose but often for other reasons.

“So we need to identify these people proactively,” she said. “Those people with substance use disorders — when they come to emergency departments — we need to connect them with outreach workers who, in turn, can connect them to care.”

That care must include expanded access to opioid agonist therapy, which means working with and training family physicians to prescribe oral therapy. Daly made it clear that addiction treatment in B.C. is going to be led by the primary care system.

“And of course we need to urgently expand injectable opioid agonist therapy, which is still only available to about 200 people in the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, almost two years into this declared crisis,” she said of the innovative program at Crosstown Clinic where clients have access to prescription drugs. “That is unacceptable and will be one of our first orders of business.”

Daly wants the number of people with access to such therapy to increase by at least 500 over the next four months.

The centre is expected to operate for at least one year. It will cost $1 million to operate for the rest of the fiscal year and increase to $2 million annually, if the government requires the centre to remain open.

The BC Coroners Service most recent statistics show more than 1,100 people in B.C. died of a suspected drug overdose between January and September of this year. More than 280 of those died in Vancouver. The coroners service found that 83 per cent of deaths were connected to fentanyl, a synthetic opioid.

mhowell@vancourier.com