In his early days as a painter, Claude Monet didn’t have much money. He embraced the modern concept of train travel — it was the 1860s and ’70s — to search out the scenes that he knew he wanted to paint.

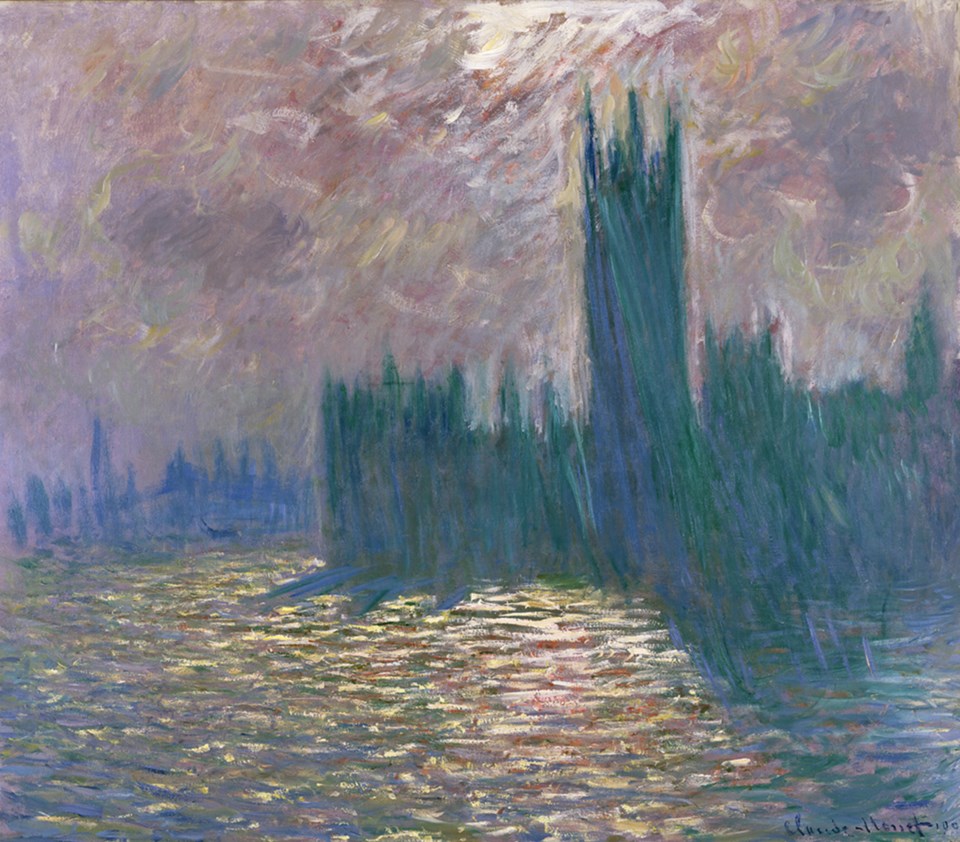

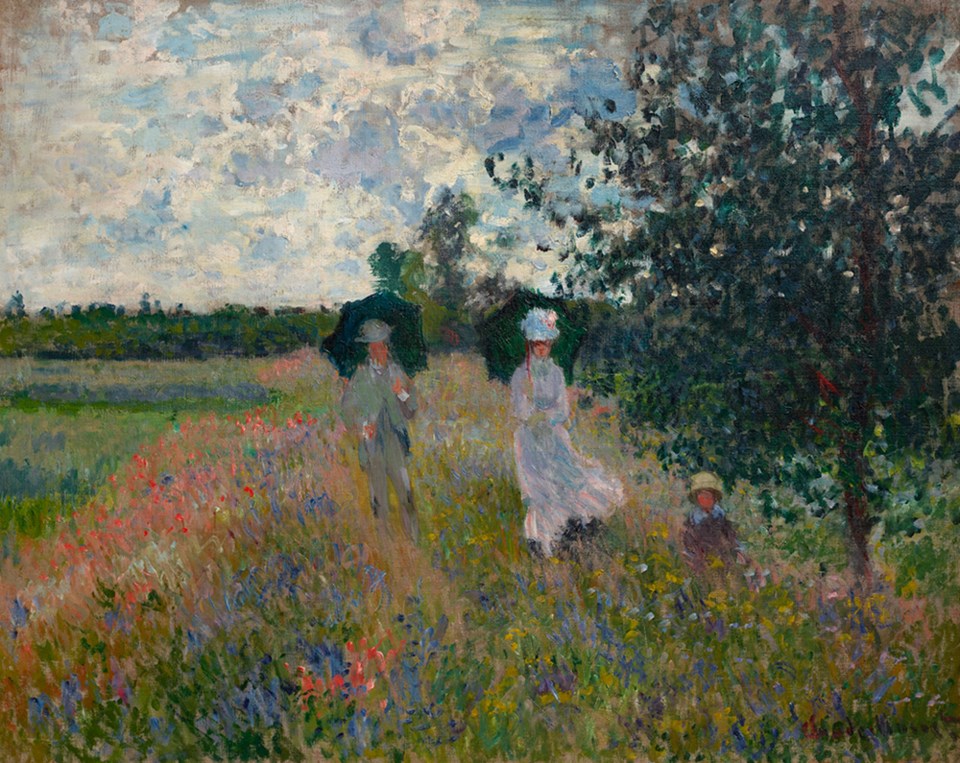

By breaking free of the restrictions of the studio, the French painter helped to revolutionize art, not just as a founder of Impressionism but also by introducing the concept of painting out of doors. Capturing the landscape itself didn’t matter; it was his impression of the landscape that propelled him. He was fascinated by the fleeting ephemera of light and mood, often painting the same scene at different times of day.

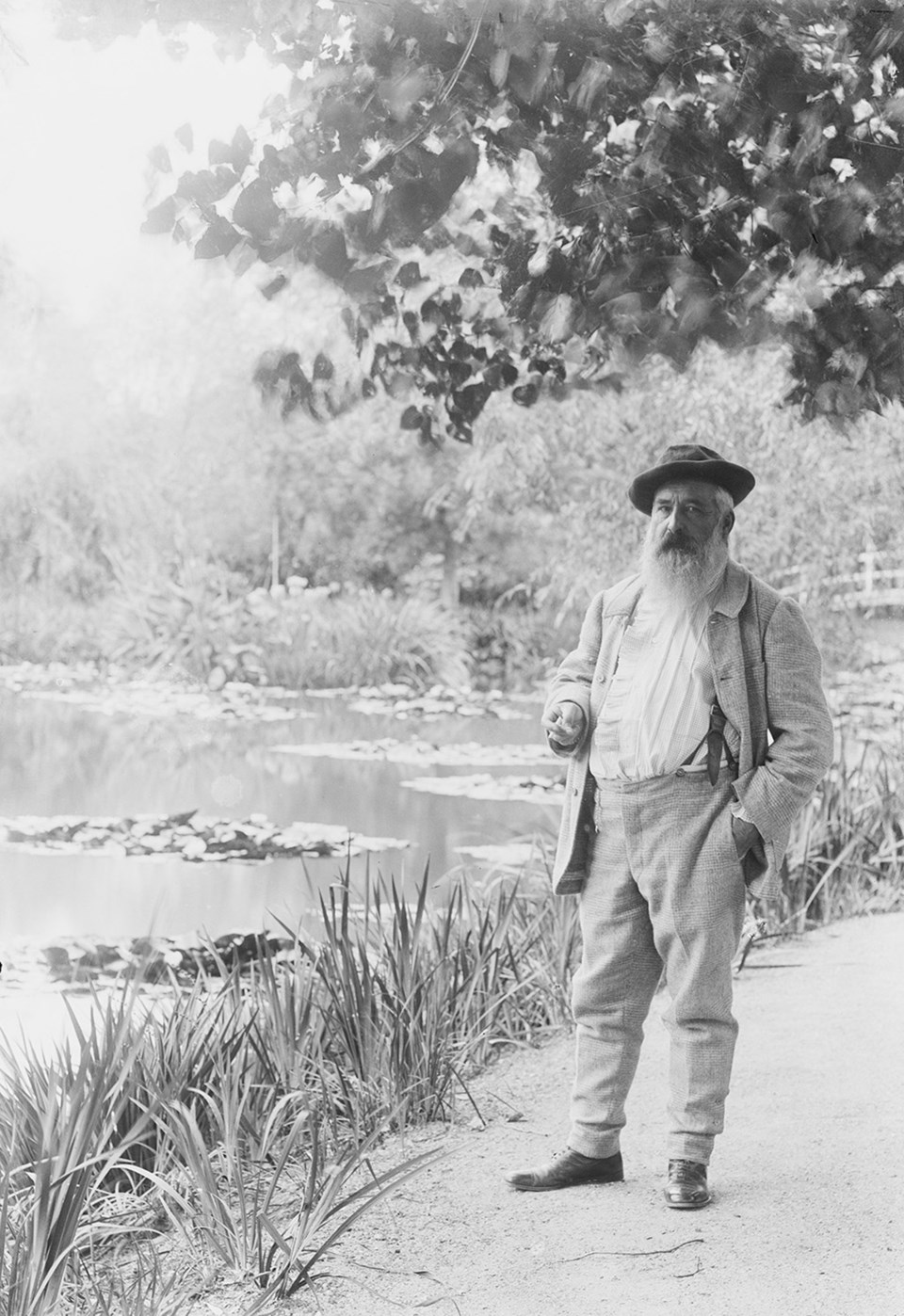

In spite of critics’ early derision, in 1890 Monet was successful enough to buy the house and two-acre property in Giverny that he and has family had rented since 1883. He set about designing and creating the gardens and ponds that he envisioned as the scenes of future paintings.

Financial independence also meant he was free from caring about what people had to say about his art. (An early patron once returned one of his paintings, thinking it wasn’t “finished” yet.) Monet kept in his house some of the paintings he loved best — paintings that weren’t put on public display until after his death in 1926.

Those paintings now provide the bulk of the Claude Monet Secret Garden exhibit at the Vancouver Art Gallery (now until Oct. 1).

Although some of Monet's most famous paintings are part of the exhibit, what’s fascinating is the way the collection allows you to experience Monet’s vision of his work through his own eyes. This is true both literally and figuratively. Later in life, Monet developed cataracts and couldn’t see colours properly. Paintings from this period are darker with reddish tones — he was painting the colours as he saw them. The success of his cataract surgery is witnessed in the vibrancy of his final painting, Les Roses, which is also the last painting in the Vancouver exhibit.

The 38 paintings are all from the collection of Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. It owns 300 of his works, donated by Monet’s son, Michel, who also donated the Giverny property to the French Academy of Fine Arts.

The museum’s deputy director, Marianne Mathieu, and VAG’s senior curator, Ian Thom, co-curated the Vancouver exhibit and led a media tour Thursday morning, two days before the June 24 official opening.

“The paintings were done for his own pleasure,” Thom said, noting that more than half of the exhibit’s paintings were done at Giverny and part of Monet's private collection. “They really were secret paintings.”

What Monet cared about was capturing light, space and colour, Mathieu says. “The flower is only a pretext for the painting.”

For instance, in the exhibit there are four paintings of the same weeping willow, all with different palates. “He forces you to go into the experience as he sees it. You have to embrace the tree — or not,” Thom says.

There are also paintings that, early opinions about Impressionism notwithstanding, really weren’t finished. Monet was painting until he died, at the age of 86, moving from one canvas to another. Vancouver’s exhibit includes a room full of paintings that show Monet as a modernist, embracing its artistic freedom. “He’s just going for the gusto,” Thom says.

Perhaps it is his waterlily paintings that prompt the most reflection about Monet’s work, not just for their wistful beauty but for their origin story. The paintings weren’t inspired by Monet’s stroll through the gardens. It was the other way around. The gardens were inspired by the paintings he first saw in his mind. He was a man in full control of his artistic vision.

A Monet exhibit of this scope “won’t happen again in Vancouver in your lifetime,” Thom said.

Starting on Saturday, June 24 and running until Oct. 1, people have an opportunity to see Monet’s Secret Garden through his eyes.

Details at vanartgallery.bc.ca.