I spent much of the Labour Day weekend periodically lurking on the Vancouver Courier’s YouTube channel.

A video I had shot called The Blob of Lost Lagoon had been picked up by National Geographic. Popular Science used it to introduce readers to the term “dragon boogers” which, apparently, is what these ancient bryozoans are sometimes called. Then the British tabloids got a hold of it.

"Video shows hideously ugly organism jiggling and pulsating as it's dragged from the water," screamed the Sun’s headline.

"Mystery of the slimy brain-like 'alien blobs' found in a Canadian lagoon that appear to be spreading," said the sedate-by-comparison Daily Mail.

Could we reach the 100,000-view mark? We did. 250,000? OMG, we did. Would it be vain to think we could reach the half-million mark? Unbelievable. There it was. As I write, the number of YouTube hits is 765,000 and I’m trying not to think of so many people watching me go into a pond to scoop up an underwater creature.

When a coworker first saw the Stanley Park bryozoan mentioned in a Facebook post, I knew it would make good video. But the idea of actually being in the video came to me after reading a New York Times story about Barbara Oakley. Her Learning How to Learn videos are wildly popular on Coursera. I watched a couple of episodes to see what she’s got going for her and concluded that she makes learning about neat things fun.

I’ve been on my own steep learning curve recently. As a traditional print journalist, how can I transform my skills for this digital age? How can I learn the language of social media — its tone, its appeal, its ability to get people to respond?

If people want to be entertained while they’re being educated, so be it. I’ll put on a pair of hipwaders and, after a few authentic squeals of grossed-outedness, put my hands around a dragon booger. Luckily for me, while I made the video fun, the colleague who edited it made it funny.

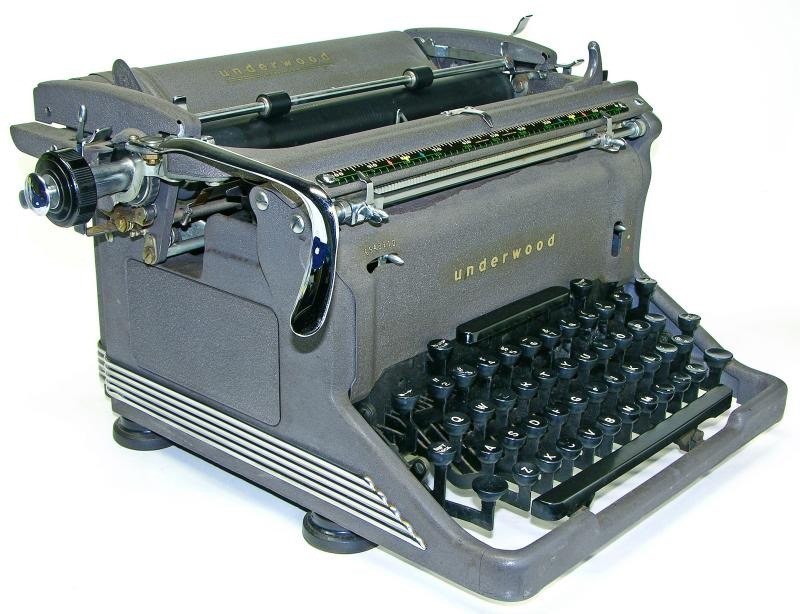

To a 20-something journalist, this would seem perfectly natural. I’m 54. I started my first reporting job on a manual typewriter. I banged words onto a yellow piece of paper, gave it to my editor who marked it up and gave it to the typesetter. The typsetter typed my words into this huge machine that spit out wet columns of type which I put on a dryer, waxed and then trimmed on the page using an Exacto knife.

When we got our first computers — Tandy K1000s — I used to grip the side of the computer to proofread my story. Writing had become such a tactile experience on that old, gray Underwood. Holding that piece of yellow paper was part of my creative process (and the stuff of bad dreams when the words disappeared from the page.)

I was at the office one Saturday when someone called to ask for our fax number. What’s a fax, I asked. It’s a way of transmitting documents using a phone line, I was told. Ha, I replied. Do you think that just because I work at a small town paper that I’m gullible enough to be taken in by such a fantastical claim?

The first week we switched to desktop computers to do layout, I thought I could never be as fast as I had been with my Exacto knife. I started a story on the front page and forgot to turn it to another page. There was no leftover strip of type to serve as a reminder.

So, like that Lost Lagoon bryozoan, I have been in a constant state of adaptation ever since I started out as a 22-year-old journalism grad. The need for adaptation isn’t new. Granted, learning how to switch from a manual typewriter to a computer was a lot easier than figuring out how to master Google analytics and write headlines that score high on the emotional reaction scale. Facebook gives me severe performance anxiety because reactions are so swift — or not. (If I’ve one piece of advice for student journalists it’s to throw in a few psychology courses.)

Will I ever have another viral video? I don’t know. At least I know it’s possible. And if you're wondering about the incongruity of wearing pearls to a pond, they were my sister Mary's. She died of pancreatic cancer when she was 58. I wear them as a reminder that every day is special enough for pearls.

Notwithstanding the British tabloids' headlines, this is not about writing for web hits only. I’ll still write my long features — I always think, “People will want to know this!” The Courier will still provide people with the thoughtful, informative stories they expect and continue to want. But if I need to attract readers to my newspaper’s website by getting them to click on a video of an icky blob, then that’s the reality I live in. I’ll adapt.