When the Canucks were good at hockey, the disagreements within the fanbase seemed a lot less contentious. Whether you think analytics are the bee’s knees or are as old-school as the University of Bologna, when your team is good, arguments can only go so far.

Now, however, the Canucks are bad at hockey, and cracks, rifts, and seams are appearing everywhere. It doesn’t take much to get Canucks fans at each other’s throats, so when “much” actually happens, like, say, trading away Jared McCann after he made the NHL as a 19-year-old, people start strangling one another.

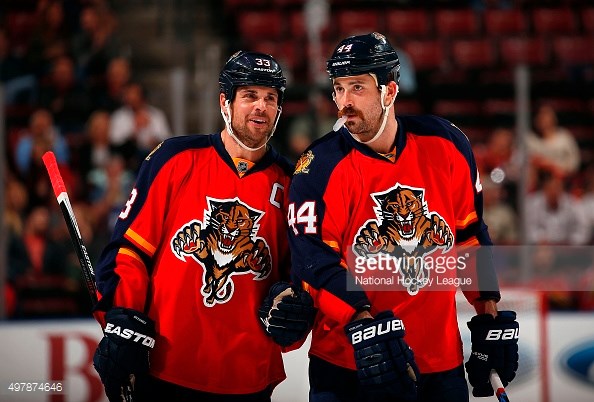

But let’s take a step back for a moment and look at some context, both for the trade and for the newest member of the Vancouver Canucks, Erik Gudbranson.

Divorced from context, this trade is still a big deal. It’s a former third-overall pick for a late first-round pick who surprised everyone by making an early jump to the NHL, and a high second-round pick, along with a couple other picks for ballast.

Still, the amount of rancor seems over the top. It’s just one trade and, by itself, it won’t make or break the franchise. Sprinkle in some context, though, and it makes sense that this trade would inspire vitriol.

For instance, this is the second time in the last four months that Jim Benning has traded away a young, potential first-line forward. It’s also the latest in a series of trades that seem to betray the rebuilding message, as the Canucks once again shipped out draft picks and got older. And it’s the latest battlefield for the analytics war, as the Canucks have made deal after deal that suggests they pay little heed to the fancier, more upscale, Shaughnessy Heights of statistics.

Gudbranson is the type of player that old-school hockey people love and new-school analytics people hate. He’s a big, stay-at-home defenceman who plays a hard-nosed physical game, with intangibles like character and leadership oozing out his pores. He’s a fan-favourite who throws hits, defends his teammates, and clears the crease. What’s not to love?

Ah, but then there are the numbers: he bleeds shots against, drags down the possession of his teammates, and provides no offence. If he’s so hard to play against, asks the analytics crowd, then why don’t his numbers prove it?

The fancy stats folk are utterly dismissive of Gudbranson, with Travis Yost particularly perplexed at the trade:

Truthfully, it’s difficult to see what Vancouver sees in this deal. If the prize is Gudbranson, well, the prize is something like a third-pairing defender. And the premium they paid – a legitimate prospect and multiple picks – is, in a word, inexplicable.

Call it like it is: Florida took advantage of a team who egregiously misvalued a defenceman to once again win a trade in striking fashion.

That’s a strong claim, that Gudbranson isn’t even a top-four defenceman, and it’s one that I was initially inclined to agree with.

But then I started thinking about context.

Looking at this past season, it’s true that Gudbranson gave up a lot of shots. Among the 197 defencemen who played at least 500 minutes last season, Gudbranson gave up the 28th most shots per 60 minutes of ice time at even-strength.

Matt Bartkowski and Alex Biega had the most and second-most shots against per 60 minutes, incidentally. And Chris Tanev had the eighth fewest, just in case you were still wondering where the problems were not located on the Canucks’ blueline last season.

So, judging solely from this metric, Gudbranson provides a small upgrade on two of the least effective defencemen in the NHL. But that’s not worth the price they paid. So let’s look at the context. In what context did Gudbranson give up those vast numbers of shots?

As you might expect, Gudbranson was deployed in a mainly defensive role. If we look at zone starts—in which zone a shift starts with a faceoff—we see that Gudbranson got far more starts in the defensive zone than the offensive zone. His ratio of offensive to defensive zone starts was second lowest on the Panthers, ahead of only Willie Mitchell.

Gudbranson’s zone start ratio last season was one of the lowest in the league. 17th among defencemen, in fact.

He also faced tough competition. Judging from the average time on ice of opposing player, Gudbranson faced the toughest competition on the Panthers, just ahead of Mitchell. With his quality of competition and zone starts in mind, we’re getting a picture of a defenceman who played tough minutes.

And he played a lot of them. Whether or not Gudbranson should be a top-four defenceman, he was fourth in minutes among Panthers defencemen during the regular season and led the Panthers in ice time in the playoffs, with the 12th highest average ice time in the NHL postseason.

So what does this context all mean? Does Gudbranson’s difficult deployment explain away his ugly possession numbers and shots against? I wouldn’t go that far. In fact, there has been a lot of work recently suggesting that zone starts have a minimal impact on possession numbers, and there is a lot of noise in quality of competition metrics that leave a lot of doubt.

But here’s something we can look at: using Corsica.Hockey’s Similarity Calculator, I found 20 defencemen whose deployment last season in terms of ice time, zone starts, quality of competition, and quality of teammates was similar to Gudbranson’s. It’s an interesting cross-section of players, including both Chris Tanev and Alex Edler.

Twenty defencemen isn’t a massive sample, but it can show us how other defencemen performed with similar usage last season. Here is the chart with all twenty plus Gudbranson, with their Corsi For %, Fenwick For %, Shots For %, and Goals For %.

With the chart sorted by corsi, Gudbranson ends up right in between two pretty interesting players: Alex Edler and Marc Staal.

Edler’s numbers get better as you take blocked shots out with fenwick and again when you take missed shots out. You see the same pattern with Chris Tanev higher up the chart, as both were very good last season at getting into shooting lanes and Tanev, in particular, is a master shot blocker.

Gudbranson’s numbers across the board, however, are very similar to Marc Staal’s. Would we be upset if Gudbranson turned out to be a younger version of Staal?

Still, Gudbranson is in the bottom half among these defencemen in each of these categories except for goals, which may have more to do with Roberto Luongo’s excellent goaltending this past season. In any case, if you want to place more importance on that number of the shot-based metrics, then you’ll have to say that Tanev is terrible, as he’s near the bottom in GF%.

Let’s take one more look at this group of defencemen by finding the average numbers from the twenty and comparing Gudbranson in a range of statistics.

Breaking the numbers down into for-and-against per 60 minutes for corsi, fenwick, shots, and goals gives us a little more detail and shows us that Gudbranson was above average in only corsi against, goals against, and goals for %.

It’s troubling that other defencemen around the league appeared to do better with similar usage to Gudbranson, but there’s just a little bit more context to draw in here.

One interesting thing to note is the one name consistently at or near the bottom of the chart, below Gudbranson’s: Willie Mitchell. At 39, the former Canuck doesn’t appear to be the defensive stalwart he once was. He was also one of Gudbranson’s most common defence partners.

There’s an argument to be made, then, that Mitchell dragged Gudbranson down, with the caveat that they faced difficult minutes together.

Gudbranson’s other defence partner last season was Brian Campbell. When they skated together, they posted a 52.5% corsi and had a goals for percentage of 62.5%.

You could argue that Campbell carried that pairing, but it seems clear that Gudbranson didn’t drag Campbell down, at the very least. When Campbell was paired with Mitchell, on the other hand, they had a corsi of 43.5%.

Gudbranson certainly played easier minutes when with Campbell—they got a lot more offensive zone starts together than when Gudbranson was paired with Mitchell—but it’s not outrageous to suggest that pairing Gudbranson with an offensive-minded partner could work out well.

Why, hello there, Ben Hutton. Didn’t see you standing there.

It also helps that the Canucks already have a pairing that can handle the tough minutes: Alex Edler and Chris Tanev. Relieved from the burden of playing primarily in the defensive zone, and matched with a puck-moving partner, Gudbranson might thrive.

It’s certainly a gamble that Gudbranson could hit his stride in Vancouver and I still question the price of acquiring him, but there is room for optimism.