Steve Suntok spends most of his weekends scouring river canyons on Vancouver Island for hints of the past.

A self-described fossil hunter, Suntok estimates he’s found about 1,000 to 2,000 fossils on the Island in the 20 years since he caught the amateur paleontology bug.

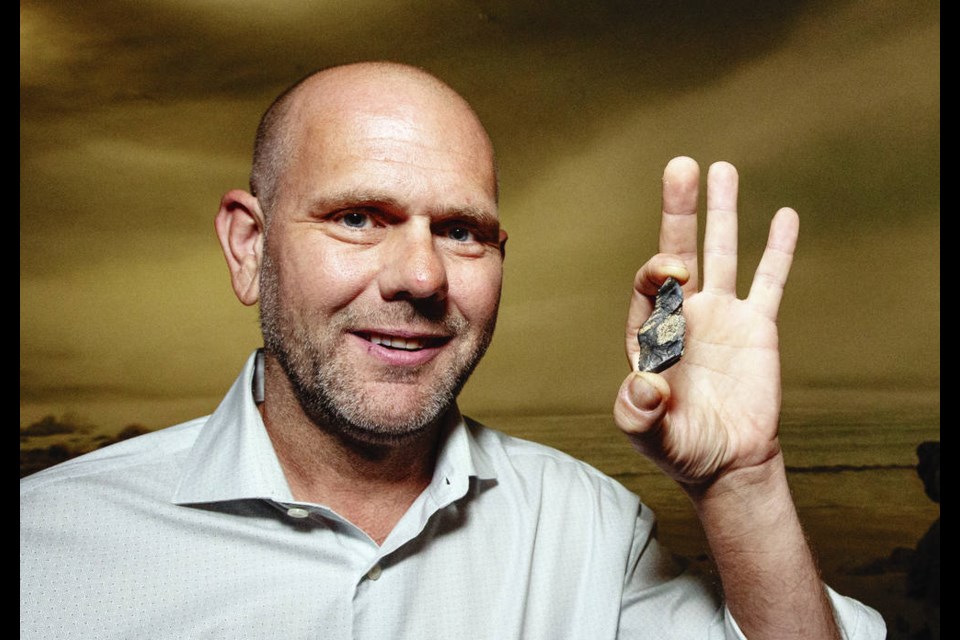

Now, for the first time, one of his finds, a 25-million-year-old dental plate of a rare and previously undiscovered fish, has been named after him.

Suntok found the fossil on a beach northwest of Sooke in 2014. He donated it to the Royal B.C. Museum, and a leading world expert on fish fossils studied the specimen in detail. In a scientific paper recently published, Russian scientist Evgeny Popov concluded the fossil was a new genus and species in the Chamaeridae family, which are cartilaginous fishes that have short rounded snouts and long tapered tails.

Popov named the fish Canadodus suntoki — Canadodus for “tooth from Canada” and suntoki for Suntok.

“It’s pretty exciting,” said Suntok, who works as a criminal defence lawyer.

Over years of frequent fossil hunting, Suntok has trained himself to notice irregularities in rock, looking for anything that appears unusual.

“The only way to get better is practise,” he said.

Suntok said he spends most weekends checking out deep gorges and canyons, where erosion can expose fossils. He rotates through about 40 or 50 different fossil sites, mostly in central and northern Vancouver Island, where fossils from as long as 80 million years ago can be found. Reaching a site often involves bushwhacking.

Erosion from wind, waves and rain is constantly exposing new rock, so Suntok regularly returns to sites to see what’s been revealed since his last visit.

“Every time you go, there’s a chance of finding something new. And that’s how I found it,” Suntok said.

On a trip to a beach near Sooke, Suntok noticed a small bit of unusual-looking rock in the sandstone of the intertidal zone. He had the fossil out of the soft rock in just a few minutes.

“I knew it was significant because I’ve done this long enough and looked at thousands and thousands and thousands of fossils. I know what’s common, and I know what’s not,” he said.

It was good timing that he found it when he did, because the area is exposed to a lot of erosion that would have quickly turned the fossil to dust, he said. “And that fossil’s gone forever.”

Marji Johns, a local paleontologist who co-authored the scientific paper with Popov, said the species Suntok found in the fossil is not well preserved in records because the fish is all cartilage, which degrades more quickly than bone.

“It’s very exciting and they’re not actually all that well known globally. There’s not a huge number of fossils of fish,” Johns said.

The fossil helps paint a picture of how these animals lived 25 million years ago, she said.

Suntok donates all the uncommon fossils he finds to the museum, which is where his amateur paleontology hobby started. He visited a fossil exhibit with his three kids, who then wanted to go out and find their own.

The recent discovery named after Suntok is the first to honour him individually, but it’s not the first time a new species has carried his family’s name.

Suntok’s daughter, Leah, happened upon a fossil about a decade ago that turned out to be a new genus and species of flightless water bird.

“We went to a beach to find some art supplies — pebbles and seaweed and stuff — because she wanted to make some art, and she found a fossil while out there looking for seaweed,” he said.

They didn’t have their tools to extract the fossil from the rock, so Suntok returned with his son, Graham, the next day to remove a 40-kilogram slab of rock and haul it to their vehicle.

The specimen was named Stemec suntokum, which recognized the Suntok family for the discovery.

regan-elliott@timescolonist.com