It wasn’t wrestling the terrorist in the street that had Mike Chapman worried. No, it was the logging truck that was bearing down on them as they held their own private rodeo, smack dab in the middle of Port Angeles’s main drag.

That was 20 years ago today, when our neighbours across Juan de Fuca Strait did what Canadian authorities had failed to do: arrest Ahmed Ressam.

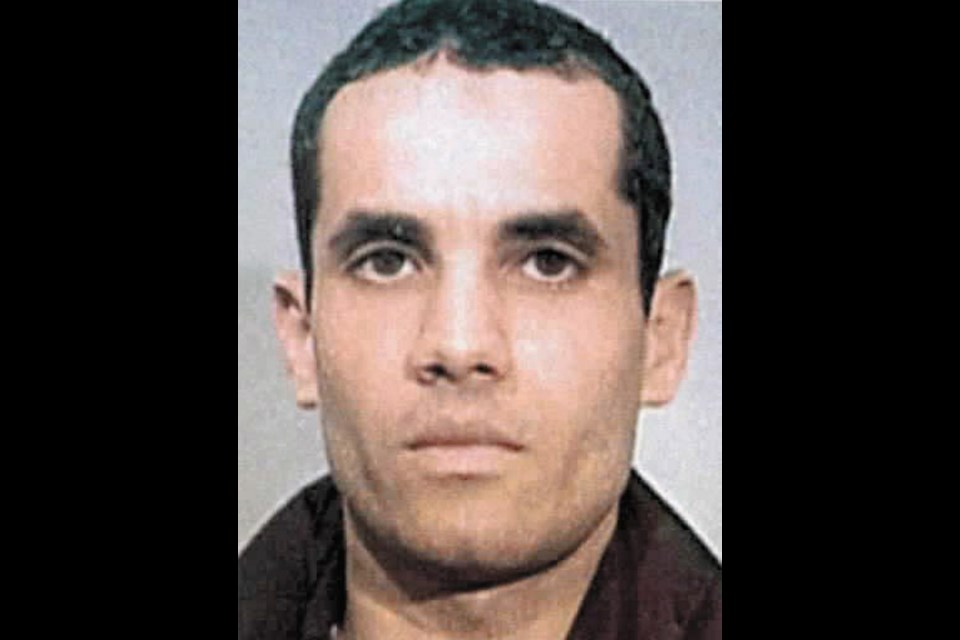

They caught him as he drove off the Coho ferry from Victoria en route to California, where he planned to blow up Los Angeles International Airport. It was the timing of that attack — New Year’s Eve, 1999 — that gave Ressam the name by which he is better known: the Millennium Bomber.

“I’m just grateful that we got him that night,” Chapman says. He’s an elected official now, sitting in the Washington state legislature, but on Dec. 14, 1999, he was a 36-year-old U.S. customs inspector in Port Angeles.

That’s how he crossed paths with 32-year-old Ressam, who had been recruited by al-Qaeda while living in Montreal.

Ressam, an Algerian, arrived in Canada in 1994 with a French passport that Canadian authorities immediately found to be fake. They didn’t throw him out, though, because he applied for refugee status, making up a story about being tortured in Algeria.

The refugee claim was rejected in 1995, as was an appeal in 1996, but Canada still wouldn’t deport him to troubled Algeria. So Ressam lived in Montreal, surviving on welfare and petty theft.

CSIS, the Canadian intelligence agency, began watching him in 1996. Police, armed with an immigration warrant and theft charges from Montreal and Vancouver, started looking for him in 1998, but by then he had gone for terrorist training in Afghanistan.

CSIS reportedly warned Canadian and U.S. authorities about the “jihad training,” but Ressam was still able to re-enter Canada in 1999, this time on a Canadian passport issued under a false name.

That December, he and another man cooked up bomb-making ingredients in a Vancouver motel before Ressam headed to Vancouver Island. He figured it would be easiest to slip into the U.S. via the back door, arriving aboard the car ferry between genteel Victoria and sleepy little Port Angeles.

A handful of U.S. Customs inspectors were on hand when Ressam rolled off the MV Coho’s last sailing of the day that Tuesday evening. It was a very light load. “Ressam’s was the last car off the ferry,” recalled customs inspector Diana Dean in an interview in 2003.

Ressam pulled up in a rented Chrysler 300 with B.C. plates, presenting Dean with a driver’s licence identifying him as Benni Noris of Montreal. (These were the days before Canadians and Americans needed a passport to cross the border.)

Where are you going, Dean asked. “Seattle,” was the one-word reply.

What for? “Visit.” Ressam was nervous, fidgeting, rummaging around on the console for who knows what.

Dean decided to do a secondary search, but first gave him a customs declaration form, mostly to keep his hands busy.

Where was he staying in Seattle?

“Hotel.”

Dean called over fellow inspector Mark Johnson, who had been to Montreal, to question the driver. When Johnson asked for ID, Ressam handed over a Costco card. Johnson took the man to a table to check his pockets.

It was still all pretty normal until the customs crew popped the Chrysler’s trunk and pulled the cover off the spare-tire well, revealing 10 plastic garbage bags packed with a fine, white powder, olive jars full of liquid and a couple of ibuprofen bottles.

A customs agent was holding the back of Ressam’s jacket, but the Algerian shrugged out of it and took off running into the night.

It was Chapman who caught up to him a couple of blocks later, catching the fugitive in the beam of his flashlight as he tried to hide under a parked car.

With his sidearm drawn, Chapman ordered Ressam to come out.

He did so, but then bolted again — highly unusual behaviour, said Chapman, a former police officer. Most criminals surrender meekly at that point.

The foot chase continued for another couple of blocks until, right at the main intersection of town, Ressam tried to carjack a vehicle that had stopped at a red light. The driver wouldn’t co-operate, though, and got her doors locked before he could force his way inside.

That’s when Chapman tackled him. “We really were wrestling in the middle of the intersection.”

Then things got complicated: “I still can’t believe I wasn’t hit by the logging truck that came through the intersection as I was trying to get handcuffs on him.”

It’s true. The big rigs are a frequent sight in downtown Port Angeles, where Highway 101 funnels through the main street. Chapman was trying to figure out if he could fit under the onrushing truck when, just in time, it ground to a halt.

They got Ressam into the back of a police car after that, though they still didn’t know what they were dealing with. “He wouldn’t speak to us,” Chapman says. “We thought it was drugs.”

In fact, they conducted field tests on the white powder, placing samples in vials that they shook vigorously. When they did so, Ressam threw himself on the floor of the cop car. “He would look up now and then and peer out the bottom of the window,” Chapman recalled. (Later, at trial, that action would be offered as proof that Ressam knew what he was transporting.)

By then the customs officers had been joined by Dean’s husband, Tony, who had come to the ferry terminal to meet her at the end of her shift. When they discovered four homemade electrical timers — circuit boards connected to Casio watches and nine-volt batteries — in the trunk, he blurted out a couple of words that Dean would not repeat.

That’s when the truth dawned. The arrested man’s name wasn’t Noris. The powder wasn’t drugs. “I knew exactly what we had,” Dean said. “My heart went right down to my toes.”

After that, all the acronyms poured in: the FBI, the ATF. Ressam got hauled away, as did the contents of the trunk. “It’s a good thing we didn’t test the ibuprofen bottles,” Dean said. They contained the detonator, a substance so sensitive that it could have sparked an explosion had they removed the bottle caps. It was later estimated that the explosives in the trunk could have caused a blast equal to that of 40 car bombs.

Even four year after the fact, Dean, a sweet-natured middle-aged woman, seemed awed by the enormity of their discovery, by what could have happened in Los Angeles. Today, Chapman echoes those feelings: “I think of the lives that were spared. The alternative would have been awful.”

About 10 years ago, he got a nice note from a California family who had passed through LAX on New Year’s Eve, 1999. Maybe they would have been victims had he and the others not caught Ressam, they wrote.

“We had a good team that night,” Chapman says. Nobody was cutting corners, trying to get home.

Ressam, who was eventually sentenced to 37 years, is being held in a maximum-security prison in Colorado.

Dean retired and moved to North Dakota, and her name is now on an anti-terrorism award handed out by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.