The following story was originally published by the Delta Heritage Society and is republished with permission.

The “Delta Stories” piece was written by society board member Nancy Demwell.

It’s about the worldwide Spanish Flu pandemic which occurred a century ago, and how it impacted the Lower Mainland including Delta.

The killer flu was a previously unknown form of influenza which struck Canada between 1918 and 1920, claiming about 55,000 Canadian lives.

An estimated three per cent of the world's population died.

In October of 1918, the Spanish flu arrived in the Lower Mainland.

Three months later, the Greater Vancouver region was one of the three areas of North America with the greatest percentage of deaths.

No other disease, war or famine killed so many people in such a short period as the Spanish flu.

In one year, a conservative estimate of 50 million to 100 million died worldwide, and an estimated 500 million were infected. In Canada, 50,000 people died, 3,500 in British Columbia alone. About 30 per cent of the province’s population of 450,000 suffered from an attack.

First Nation peoples had nine times more deaths than non-indigenous populations in British Columbia.

It is theorized that First Nations had not had the exposure to influenza that non-indigenous people had and therefore hadn’t developed antibodies, but they were also more afflicted by secondary infections attributed to tuberculosis and pneumonia.

It was a baffling disease at that time. It was not the children and elderly who were most vulnerable to the dreaded influenza but young adults in their 20s and 30s.

In a research breakthrough in 2014, it was found that exposure to the influenza strain between 1890 and 1900 and then to the Spanish flu of 1918 created an immune system overreaction described as a “cytokine storm,” which resulted in the premature deaths.

There were no antibiotics or vaccines at that time.

Library and Archives Canada

Greater Vancouver community health officials were somewhat prepared for the Spanish influenza attack when it arrived, having had the examples of the pandemic’s impact on eastern North America. However, the reality of its arrival was something else.

The first case hit Vancouver on Oct. 5, and by Oct. 22 there were 522 cases.

Three months later, 900 deaths had been recorded.

As health-care facilities in Vancouver and New Westminster filled beyond capacity, school gymnasiums and meeting halls were adapted into influenza hospitals.

With many doctors serving overseas during the First World War, the ratio of patients to doctors was close to 700 to one.

Doctors and nurses collapsed from exhaustion and the St. Andrew’s Ambulance service stepped in to train volunteers to nurse the sick.

Along the Fraser River, canneries were just wrapping up their season, and as incidents of flu began to occur, the transient summer workers left to return to their homes, in some cases taking infection with them to other communities.

In North Delta, Ladner and the communities of Surrey, schools and other large meeting places such as churches and meeting halls were closed.

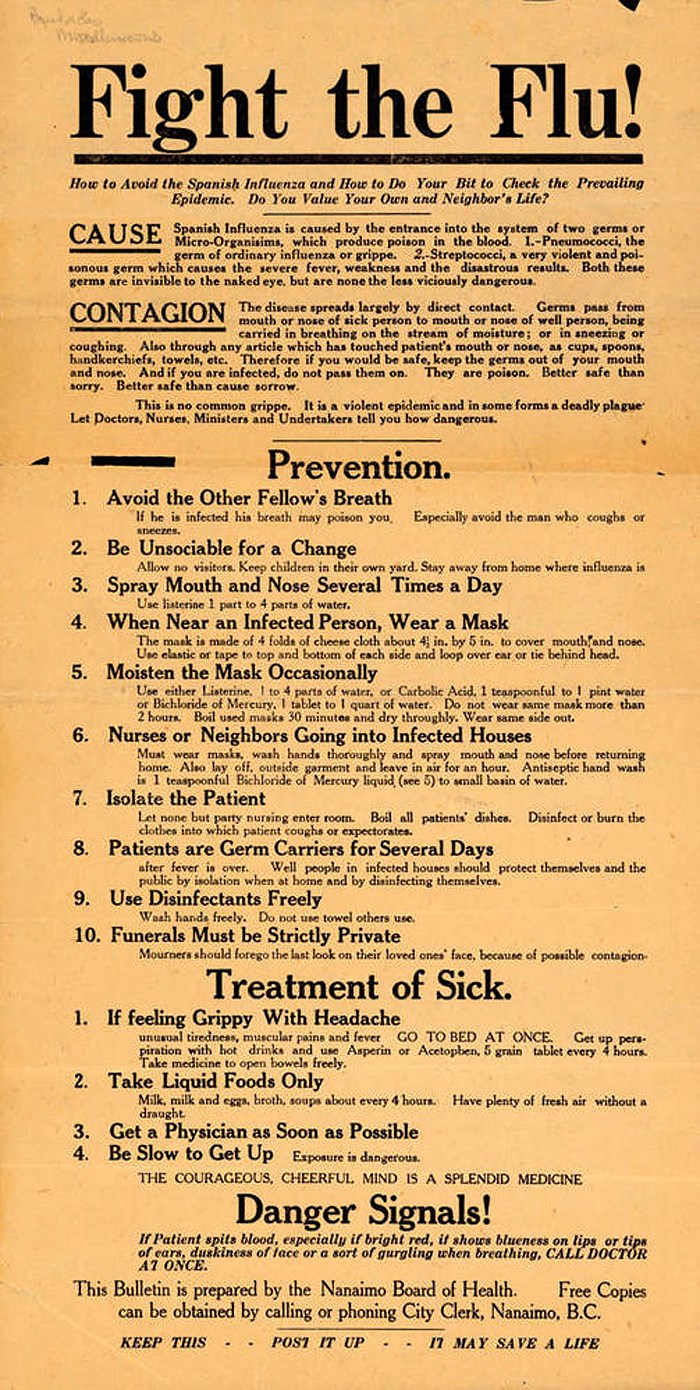

The public was discouraged from travel and public health pamphlets instructed readers how to make influenza masks to be used outside the home.

Neighbours and friends would write to each other rather than visit, and many people “baked” their letters before opening them.

Even in these hard times, people reached out to assist others in need.

The Rotary Clubs assisted transporting family members of the gravely ill to influenza hospitals, and the Imperial Order of Daughters of the Empire prepared food for invalids. Many neighbors and friends helped nurse those that were afflicted or helped to dig graves when necessary.

Royal BC Museum and Archives

If you have a Delta Story to share please contact the Delta Heritage Society at [email protected]