She’s an insurance adviser who writes poetry.

In mid-conversation, Me-An Laceste asks: “Do you, by any chance, have love letters?”

A businesswoman, dancer and world traveller, Laceste is hunting yesterday’s passion locked in ink and pulp. Words that make you blush. Letters that carry a memory of the match you could never strike. She wants to inspire an appreciation for love letters in the next generation of unrequited romantics and undiagnosed poets, she explains.

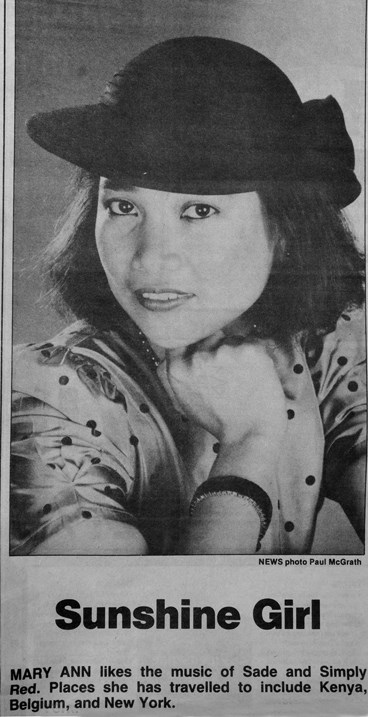

In 1993, Laceste was a Sunshine Girl in the North Shore News.

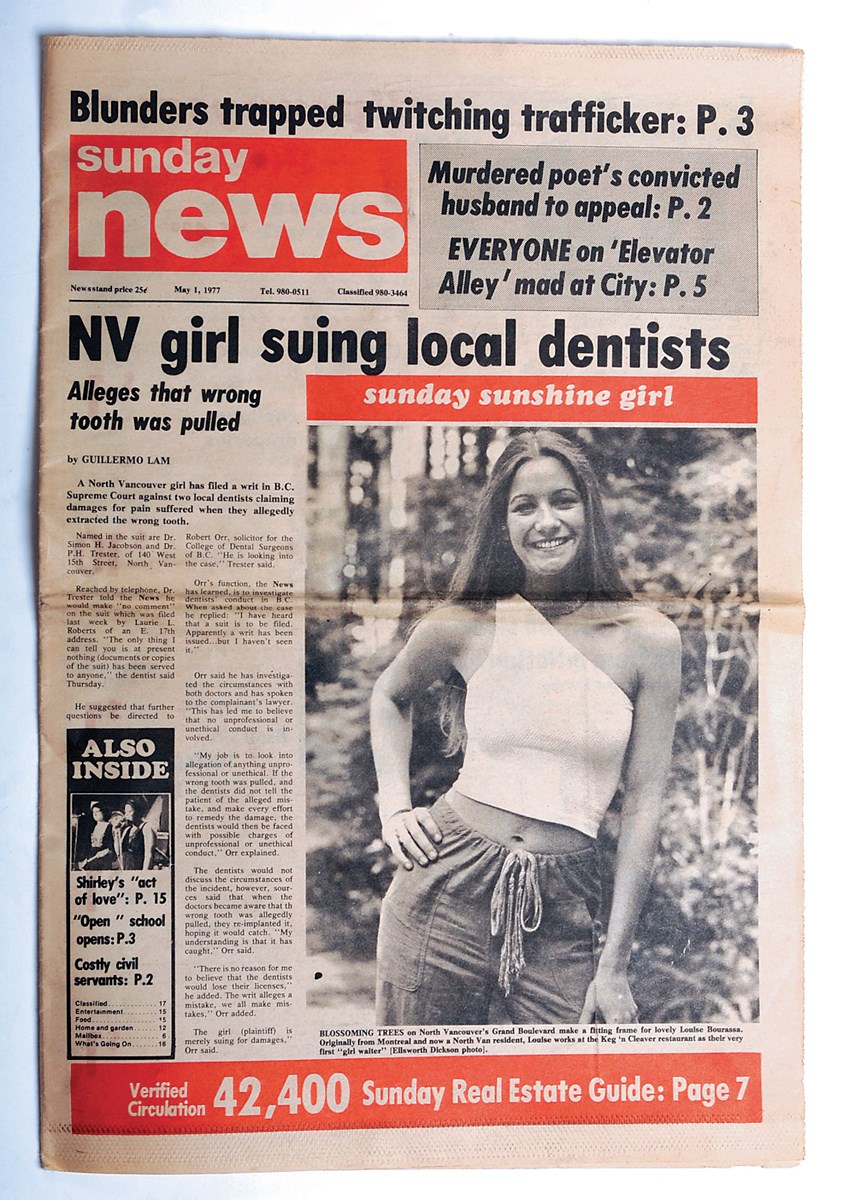

For 30 years, the Sunshine Girl was standard issue in the North Shore News. The photo – sometimes suggestive, usually not – of a smiling woman or teenage girl dominated one-quarter of a news page.

“Oh my gosh, to be young again,” Laceste marvels, looking at her beaming black and white face preserved in a photo album.

When Laceste posed, the paper encapsulated her life in two declarative sentences. “Her favourite singer is Sade,” the writer offered. The other sentence noted Laceste likes: “diversity in culture, hats.”

It was like the paper cropped out Laceste’s life to make room for her face.

To be fair, Laceste offers, she still likes hats.

“I’m wearing a hat right now,” she laughs.

She must’ve been bold back then, she says. And young.

“I’m still young at heart,” she adds.

But while the former Sunshine Girl is still youthful, the Sunshine Girl feature is an artifact from an era when the sun never set on questionable taste.

* * *

John: I want to hold a mirror up to life. I want this to be a picture of dignity! A true canvas of the suffering of humanity!

LeBrand: But with a little sex in it.

John: A little, but I don’t want to stress it.

– Sullivan’s Travels, 1941

* * *

As thunder follows lightning and regret trails a third martini, criticism stalked the North Shore’s new newspaper in 1971.

Why, readers wanted to know, was this newly launched paper stuffed with advertising?

To that query, the paper’s founder and publisher Peter Speck offered four words: “No ads, no eats.”

To carve out a share of the market, Speck’s fledgling paper co-opted an idea pioneered by tabloid merchant and future Fox News master of the universe Rupert Murdoch.

From the time the ink dried on his first edition in 1970, Murdoch’s newspapers were notorious. “No self-respecting fish would want to be wrapped in a Murdoch paper,” Chicago columnist Mike Royko once declared.

To boost circulation, Murdoch put partially clothed pinup girls on page 3 of Britain’s Sun newspaper.

The idea spread.

In Toronto and Calgary, newspapers offered an unflinching view of crime and politics. Only now with a little sex in it.

It was a “sign of the decline of journalism,” summarizes Peg Fong.

Fong, a Langara journalism instructor, had a front row seat for that decline when she was a child working at her family’s corner grocery store in Calgary.

Some customers grabbed the Calgary Herald. But when it came to the Calgary Sun, the men stopped, flipped to page 3, and looked.

“If they liked what they saw, I sold a newspaper,” Fong remembers.

It was a little puzzling, Fong recalls.

“I never aspired to be on page 3.

I always wanted to know: ‘How did you find them?’”

What boys like

In 1983, everybody wanted to be a Sunshine Girl.

“That was what everybody wanted do,” Angie Schoening emphasizes. “Everybody.”

Shoening remembers being 15 or 16 when her photo was taken.

“I was trying to be all professional,” she says, describing her white lacy shirt and black pleated pants.

“I looked so mature,” she says, her voice dissolving into peals of laughter.

At the time, she thought being a Sunshine Girl might advance her career.

“My mom was trying to get me into modeling,” she says. “It was a little stepping stone in my mind [and] in her mind.”

The interval between photo shoot and publication was excruciating.

“I was on pins and needles, dying to see it,” she says. “The week my picture was in the paper I was very popular with the boys.”

Katherine Spong was about 19 or 20 when she was persuaded to be a Sunshine Girl by the paper’s newest photographer.

“I got talked into it because Terry Peters was a personal friend,” she remembers.

Spong is naturally introverted but, she says, she trusted Peters.

“I don’t know if I would’ve done it with anybody else.”

Peters took photos of Spong in Bridgman Park.

“He knelt in dog crap when he was taking the picture,” she says. “I laughed my ass off about that.”

The photos were revealing, Spong remembers.

“A little more risqué than I’d expected,” she summarizes.

Her family teased her after the photo was published. Everyone seemed to recognize her. But then, she points out, everybody already knew her.

“That’s when it was a small town.”

Spong lives in Prince Rupert now. “It reminded me a lot of North Van when we were kids,” she says.

Looking back, the Sunshine Girl feature seems light and fun.

“There’s so many more important things going on in the world than having some young thing in the paper,” she says. “In my case, it was good for a giggle.”

Searching for sunshine

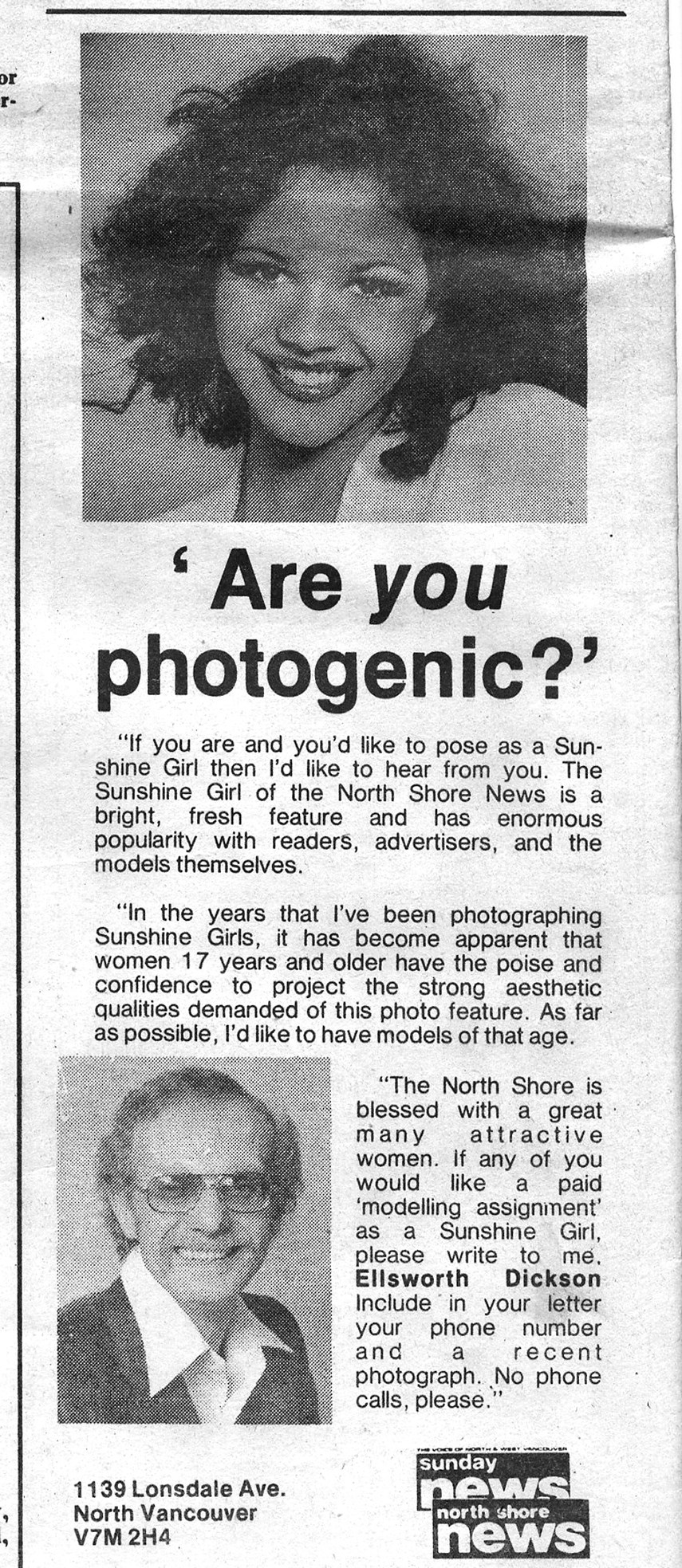

The North Shore News headline demanded: “Are you photogenic?”

Below the headline was a recruitment pitch for women “17 years and older” with poise and confidence.

For some girls and young women, being a Sunshine Girl came with prestige, and perhaps, one wondered, chauffeur service?

North Shore News photographer Mike Wakefield remembers waiting for a model one evening. He called.

“Are you heading over now?” he asked.

“I’m waiting,” she told him.

“What do you mean?”

“You know, the Sunshine Girl cab.”

The Sunshine Girl cab?

Wakefield eventually realized she must mean the Sunshine Cab company – which didn’t have a thing to do with Sunshine Girls.

“It hasn’t come to pick me up,” the model reiterated.

Wakefield sighed. “I don’t think it’s going to.”

Sending the right message

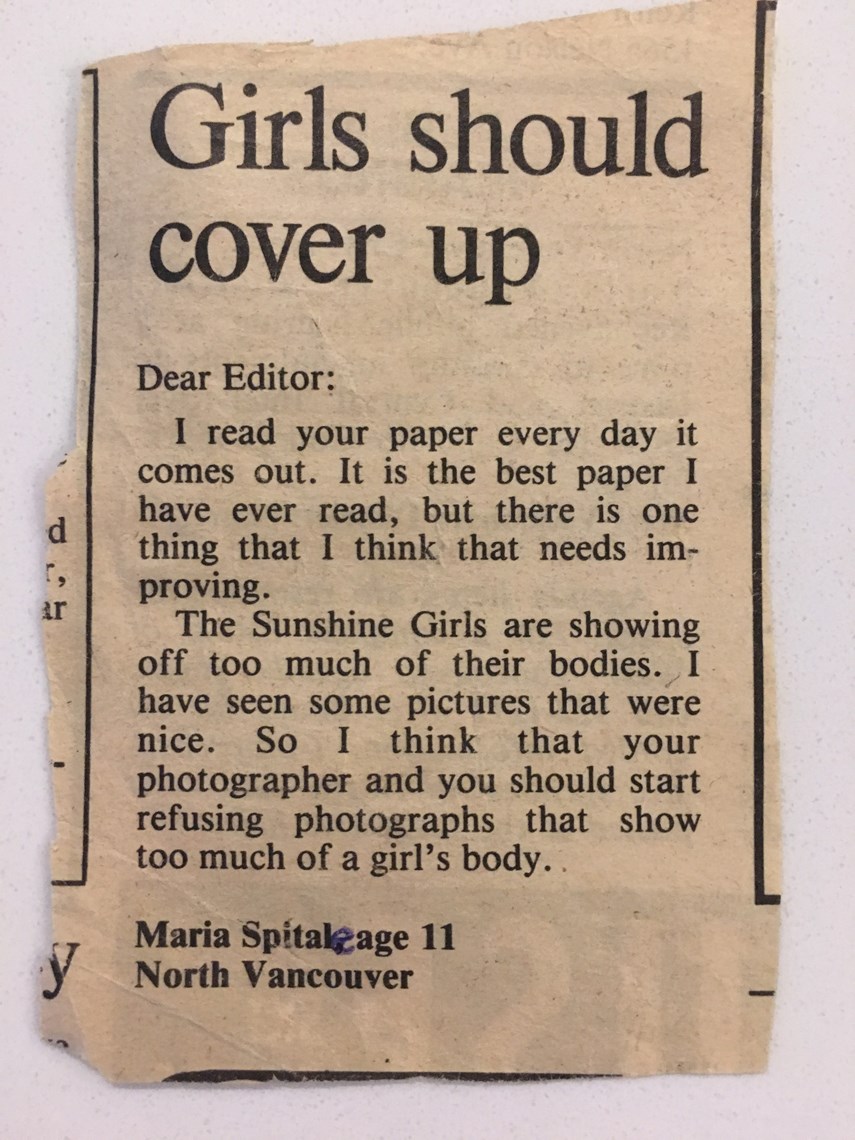

At 11 years old, Maria Spitale-Leisk hadn’t watched any R-rated movies or seen any steamy TV shows. The only provocative images to make it past the doorstep of her conservative, “church on Sunday, Catholic school” Blueridge household were in the North Shore News.

At her parents’ urging, she wrote a letter to the editor.

The North Shore News “is the best paper I have ever read, but there is one thing that I think needs improving. The Sunshine Girls are showing off too much of their bodies,” she wrote in 1990.

Nearly 30 years later, former North Shore News reporter Spitale-Leisk wonders if she sounded like a narc. “Oh, there’s the killjoy,” she laughs.

Now webmaster for North Vancouver School District, Spitale-Leisk remembers what was largely a “kid-friendly” publication.

There were great photos and stories about people she knew. And then, there was the Sunshine Girl.

“As a child, it was a jarring contrast to see these provocative images share a space with pictures of kids playing in the park,” she recalls. “I just felt it didn’t belong in a community newspaper. It wasn’t the Daily Mirror.”

It wasn’t about shaming anyone who posed, she says. “The sexist tone of the feature was sending the wrong message to young readers,” she explains. “If you fit our beauty criteria then you deserve to be in the spotlight.”

She was proud to see her letter in print.

“It felt empowering as an 11-year-old to have my voice heard,” she recalls.

Still, it would be almost a decade before the North Shore News scrapped the feature.

Bikini overload

In the 1970s, the North Shore News referred to local governments as “city fathers.” Council coverage was provided by, “Heather Jeal, girl reporter.”

One 1979 edition showed three women in bathing suits (four, if you include a fitness centre’s ad) over three pages.

Coverage of the destruction of squatters’ homes at Maplewood Mudflats refers to a resident as “Pretty” Colleen Wallace.

Cindy Goodman was a 20-year-old aspiring photog when she walked into the North Shore News office in 1987.

They were looking, as always, for more Sunshine Girls.

“I thought, well, that would be a good in,” she says.

The likes/dislikes conversation quickly segued into a photography discussion with Terry Peters, who was handling the hiring. The housing market was booming and the North Shore News needed real estate photos.

Luckily, Goodman just happened to have handy a portfolio of her photos.

“Do you still want to pose for Sunshine Girl?” Peters asked.

“I said, ‘Sure!’ So I did, just because I was young and dumb,” Goodman laughs.

She was a Sunshine Girl. And for the next 32 years, she was a staff photographer.

Sunset

By the 1990s, the Sunshine Girl supply line was getting longer and harder to maintain.

Local girls didn’t want to pose anymore, Goodman says. The reason so many models listed “bad drivers” as a dislike is because they were trucking in from Abbotsford, Langley and Richmond.

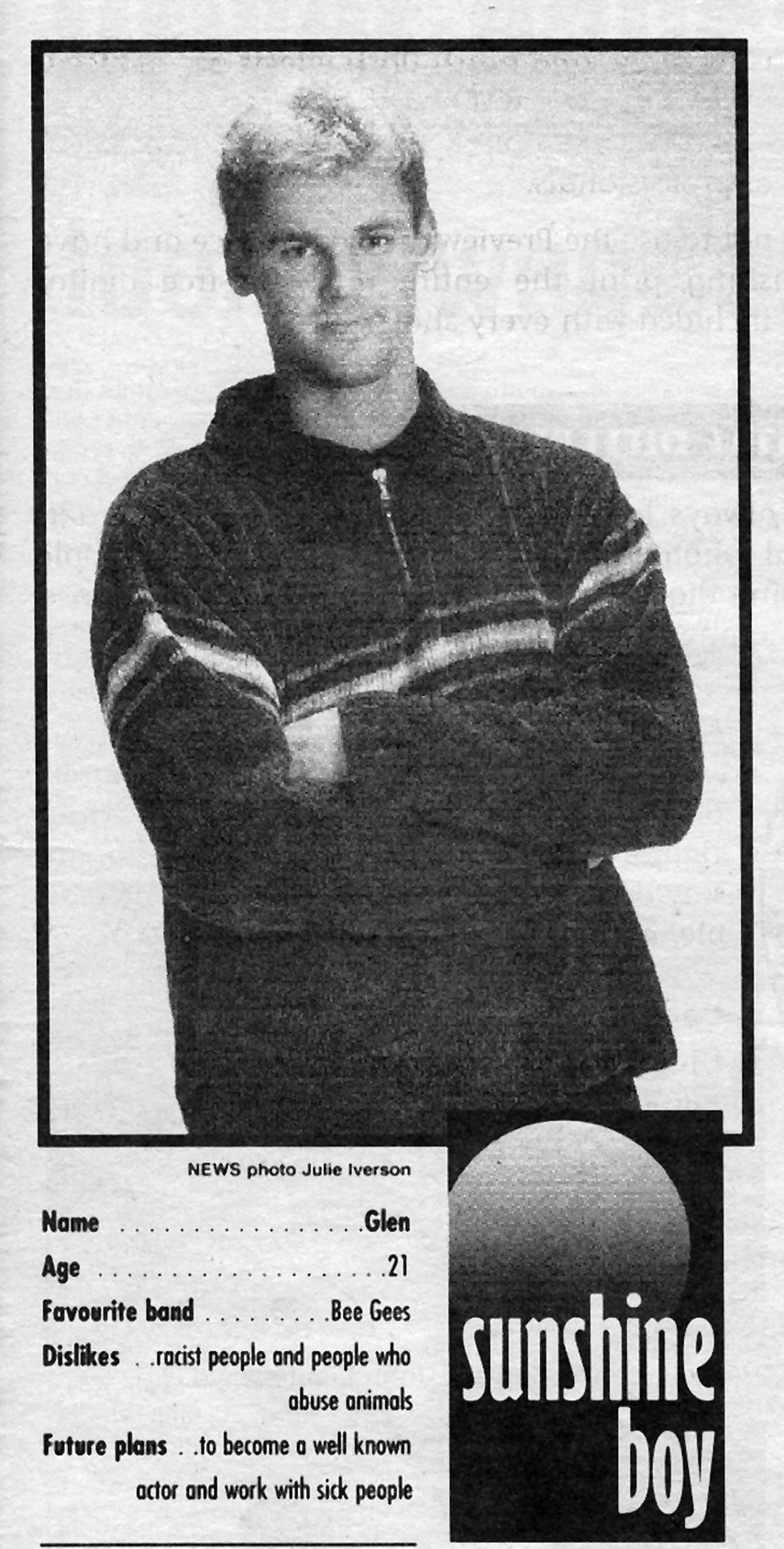

In 2000, the paper offered a paean toward equality with the Sunshine Boy. Readers met Adam, a history buff who disliked standing still, spiders and research papers.

But despite those efforts, the feature seemed increasingly anachronistic. Women weren’t content to be seen. Or at least not just seen.

In May of that year, Sunshine Girl Michelle listed her likes as: “returning the environment to its natural state.”

By the end of the year, the Sunshine Girl died a “natural death,” Goodman grins.

“We didn’t miss it at all.”

Peg Fong echoed that sentiment.

“There is no place to show women on page 3 of a major print newspaper,” Fong says. “Maybe that’s too definitive but I don’t care. . . . You do not need to show women and exploit women that way.”

There are other ways to attract readers, she suggests.

“Do good journalism.”

The Sunshine Girl was something different, Me-An Laceste reflects. And maybe it could be different again.

“It’s not bad news, it’s not a political issue, nothing but: ‘Oh, look at that smile.’”

Maybe, Laceste says, the Sunshine Girl could come back. The accompanying write-up could be longer. And the “girl” could be an 80-year-old woman. It would send a message that growing old can be a beautiful thing, she says.

After posing in the North Shore News as a teenager, Schoening embarked on a short, somewhat unhappy modelling career.

“People being very critical of you and I was like, ‘Screw you.’”

Still, she loved being a Sunshine Girl.

“I have nothing negative to say about it at all.”

She works as a HandyDART driver these days. She has a son and a daughter. Her daughter, she notes, is at the same age Schoening was when she was a Sunshine Girl.

And would she be OK with her daughter posing?

“I could ask her,” Schoening replies. “She would be a perfect Sunshine Girl. She’s gorgeous.”

This story was included in our 50thAnniversary Issue, published Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2019. Click here for more stories from this special edition of the North Shore News.