Fishermen of all stripes — commercial, First Nations and recreational — may want to brace for what could be an epic bad year for sockeye.

The combination of closures on chinook and drastically lower-than-expected returns of sockeye are building up to what could be a year of idle fishing boats.

This year’s sockeye return is a subdominant year, so it was expected to be lower than last year’s return.

But in-season forecasts are now suggesting that Fraser River sockeye returns will be so poor this year that a full closure can be expected. That includes First Nations food, social and ceremonial fishing.

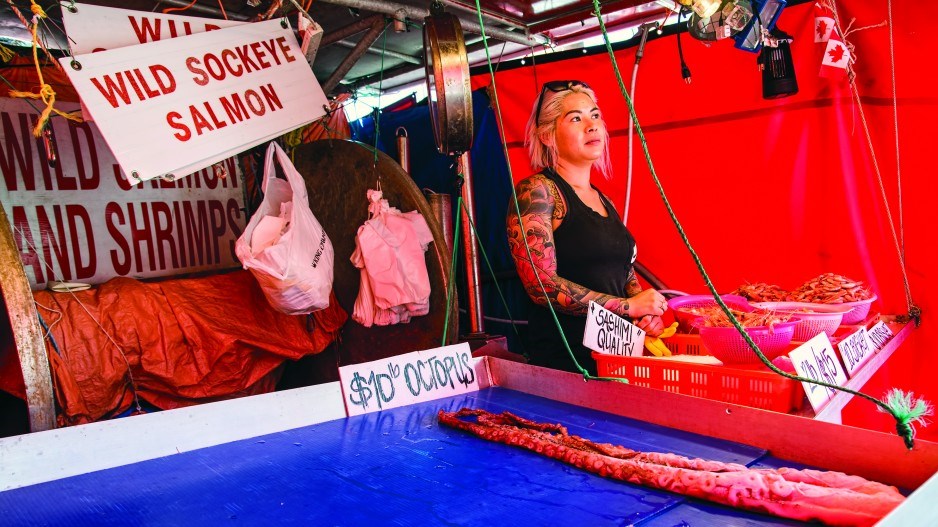

Bristol Bay sockeye in Alaska, meanwhile, continue to return in explosive numbers, which explains why consumers in B.C. can still buy sockeye at such reasonable prices — it’s Alaskan sockeye they are buying, not B.C. salmon.

Lower Fraser River First Nations are already calling this year’s fishing season “a disaster,” in part because of closures to protect chinook stocks.

Recent test fisheries suggest this year’s Fraser River sockeye return could be a repeat of 2016 — when only 860,000 Fraser River sockeye returned — the lowest return on record.

The pre-season forecast for 2019 was 1.8 million to 14 million Fraser River sockeye, with a median forecast of 4.8 million sockeye and five million pink salmon.

But last week, the Pacific Salmon Commission (PSC) dropped the forecast to 1.6 million sockeye, and even that target may not be met.

“With that reduced run size of 1.6 million, there would be no marine and Fraser River sockeye directed fisheries this year,” said Catherine Michielsens, the PSC’s chief of fisheries management science. “And also, for First Nations, food, social and ceremonial sockeye fisheries remain closed as a result.

“The news may get even worse,” she added.

As of last week, 50 per cent of Fraser River sockeye should have shown up, but as of Aug. 14, only 15 per cent had.

“So, in order to still have a run size of 1.6 million, we need to start seeing substantial numbers of additional salmon arrive soon, or the run size will be downgraded further,” Michielsens said.

Based on the age of most of this year’s returning Fraser River sockeye, it may be that the fish that were supposed to return this year may be still at sea and will stay there for another winter.

Sockeye generally mature and return in their fourth year. But when maturation is delayed — possibly due to a lack of food — they can spend an extra year at sea. That appears to be what happened with this year’s return.

“Normally, in a year like this, we would expect the majority of the returns to be four-year-olds,” Michielsens said. “But actually what we’ve seen so far is the majority of the returns have been five-year-olds. So they’re offspring of the 2014 Shuswap dominant run.”

So it may be that Fraser River sockeye that normally would have returned this year have been stunted in their maturation and may spend another year at sea. Or they may have simply not survived predators or competition for food at sea.

This year’s Chilko Lake sockeye returns were expected to be substantial, based on the number of fish that made it out to sea in 2017. An estimated 71 million smolts were thought to have migrated to sea in 2017.

“That’s more than twice than the cycle average, so it reflects a high freshwater survival,” Michielsens said.

“So there’s nothing wrong with the freshwater survival of the fish that are currently returning. So the low returns that we’re currently seeing would lead us to believe that the problem lies in the marine environment.”

There is growing evidence that the Pacific Ocean has reached — or is close to reaching — the limits of its carrying capacity, and that pink salmon are flourishing at the expense of sockeye and other salmon species.

Pink salmon are naturally the most abundant species of Pacific salmon, and their numbers have been artificially boosted in the last couple of decades through commercial hatcheries in Alaska and Russia.

Sonia Batten, a Canadian researcher with the UK-based Marine Biological Association, and Greg Ruggerone, fisheries researcher at Natural Resources Consultants, have collaborated on studies that suggest pink salmon abundance may be correlated to low abundance of other species.

“We did find an impact of pink salmon abundance on delayed maturation [of sockeye],” Ruggerone said. “So in other words, when there were lots of pinks out there, sockeye in the Fraser tended to delay and come back as five-year-old fish.”

Batten has identified a see-saw relationship between zooplankton and phytoplankton cycles that appear to coincide with pink salmon cycles, although Batten cautioned that there are other factors, like ocean temperatures, that could partially explain the oscillations.

Pink salmon are most abundant in odd-numbered years. Between 2000 and 2014, Batton identified cycles in which phytoplankton spiked and zooplankton (which eat phytoplankton) plummeted in odd years, which is when pinks (which eat zooplankton) are most abundant.

“For me, I saw this alternating pattern that really could only be attributable to pink salmon,” Batten said.

Too many pinks eating too much zooplankton — as well as other invertebrates that also eat zooplankton — could mean other species, like sockeye, aren’t getting enough to eat.

“In years with high pink salmon abundance, they’re stripping out the animal plankton that a lot of other species would be dependent on,” Batten said.

But if pink salmon are having an impact on Fraser River sockeye, why does Bristol Bay Alaska continue to produce near-record returns? Bristol Bay fishermen just recently wrapped up one of their most successful harvests — 42 million sockeye.

One explanation is that those Bristol Bay sockeye don’t face the same challenges as Fraser River sockeye, which may include:

- Warmer waters

- Higher predator populations (seals, sea lions, etc.)

- Fish farms along migration routes

A 2012 paper led by Brendan Connors, with contributions by Ruggerone, came to an “all-of-the-above” conclusion, with an emphasis on pink salmon competition.

“Our findings suggest that the long-term decline (of Fraser River sockeye) is primarily explained by competition with pink salmon, which can be amplified by exposure to farmed salmon early in sockeye marine life, and by a compensatory interaction between coastal ocean temperature and farmed-salmon exposure.”

Ruggerone points out that, Bristol Bay notwithstanding, some sockeye runs in other parts of Alaska have also experienced dramatic declines in recent years. Chignik sockeye returns have been poor in recent years, for example.

“The past two years — last year and this year — there’s no commercial harvest, and they’re barely meeting their escapement goals,” Ruggerone said.

Click here for original story.