Vancouver is growing, and with growth comes change.

Every day, close to 100 people move here; some from other parts of the province, some from other parts of the country and some from other parts of the world.

According to BC Stats, this growth will balloon Metro Vancouver’s population by 38 per cent to 3.4 million over the next quarter century. In Vancouver proper, that means an additional 160,000 people will be calling the city home by 2041.

However, with the skyrocketing price of real estate and rock bottom rental vacancy rates sitting below one per cent, the question of where to house the Vancouverites of the future remains unclear. Just this week, the US group Demographia named Vancouver the third most unaffordable city to live in, in the world.

“The city is undergoing massive change, so we’re at crossroads right now,” says Dr. Gregory Dreicer, the Museum of Vancouver’s director of curatorial and engagement. “The decisions we make today about how to accommodate that growth will affect this city for generations to come.”

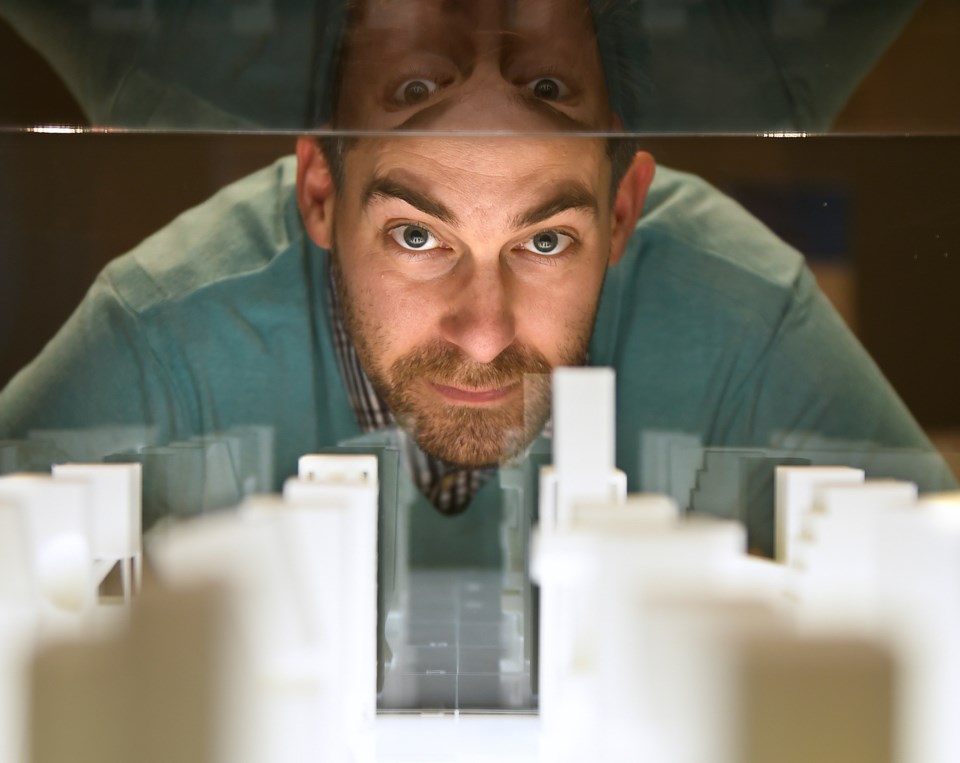

Museum of Vancouver’s newest exhibition, Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver, presents more than 20 different visions for the future of Vancouver from the city’s leading architects, urban planners and designers. Among the multimedia scenarios is a model for a 2,500-foot vertical city; a strategy for a post-disaster transportation network that caters to bicycles; and a proposal for a network of floating barge parks.

“The whole reason behind it is, if you asked any Vancouverite what is their biggest fear or anxiety about living in Vancouver, affordability or affordable housing would be at the top of the list,” says Dreicer, “And related to that, even though people might not say it, is transportation, density, public space.

“All of these things are closely related for people.”

The scenarios presented in the exhibition represent solutions as well as provocations; thought experiments designed to challenge how we look at the city around us, and broaden our minds to the possibilities of what Vancouver could become.

“Some of them are wild concepts, fantastic ideas,” says Museum of Vancouver spokesperson Myles Constable. “It couldn’t be more apropos.”

The Challenges

What draws many to Vancouver – the proximity to mountains and ocean – has also contributed to its growth woes. Hemmed in on all sides by rock and water (as well as protected agricultural land and an international border), if Vancouver is to grow, it will need to grow up, and that means more densification.

Suburban, low density, single-family homes still make up the vast majority of Vancouver neighbourhoods, notes Dreicer. Downtown is already the second-most densely populated area in North America after Manhattan, so that increased population will have to settle in surrounding areas.

“For a lot of people, Vancouver is the downtown,” says Dreicer. “But 90-95 per cent of the land is suburban low-rise or industrial, and that’s where the future lies.”

What form that will take remains to be seen. And the expectations of what housing should look like vary greatly among Vancouverites.

“The idea of ‘home’ is very much rooted in what you’re used to, what you grew up with,” says Dreicer. But given that 35 per cent of Vancouverites were born outside of BC – the fewest native-born residents of any major city in North America, proportionally – what people grew up with differs dramatically, and so too does their notion of what a home looks like.

For many Vancouverites, the single-family detached house is what they think of as normal. But that mode may be outdated and incompatible with our rapidly growing city.

As one enters the exhibition, one must first pass through an oddly familiar, though seemingly out-of-place room. Designed to look like the omnipresent condo sales offices that pop-up and then quickly disappear from storefronts around the city, the “presentation centre” uses the ubiquitous visual language of real estate marketing not to sell you a condo, but instead to sell you the idea of Vancouver’s future.

In a city where half of all conversations seem to begin with real estate, it seems fitting the exhibit would begin here.

“We want to shift the conversation from real estate to Vancouver,” explains Dreicer. “Real estate is a part of it, but it’s a bigger story than that.”

Lining the wall are hundreds of photos of every single common style of housing found in Vancouver; post-war bungalows, Vancouver Specials, turn-of-the-century heritage homes, condo highrises, even a homeless person’s tent. Every one of them is someone’s home.

“We’re asking people, what’s your future, what are you going to choose?” says Dreicer. Traditional low-density modes of housing present great challenges to building the Vancouver of the future, encouraging sprawl and an inefficient use of resources. But while highrises can provide more affordable housing, they can also bring with them issues of overcrowding, social isolation, and a lack of public space.

“Whatever it is we choose, it’s going to impact us, it’s going to impact our children, and even our children’s children.”

The Visions

Focusing on the themes of affordability, transportation, density and public space, the 20-plus scenarios presented in the main exhibition area of Your Future Home each provide a different path into the future.

Co-curated by Vancouver architect Bruce Haden, the exhibition was put on in partnership with the Vancouver Urbanarium Society, a Vancouver-based non-profit comprised of architects, designers and urban planners who aim to “foster intelligent city building.”

The visions vary greatly in scope. Some provide a step-by-step illustration of how densification will look on a block-by-block basis. HCMA Architecture + Design’s proposed recreational platform in Coal Harbour reimagines the Vancouver waterfront with access for swimming and recreation. Projected on screens are illustrations that demonstrate just how unaffordable Vancouver has become, with an imaginary line moving eastward across Vancouver, marking where the average price of a home is $1 million or more.

Perhaps the most impressive is the 2,500-foot Vertical City scenario from Henriquez Partners Architects. The model presents what Vancouver would look like if the downtown section of Granville Strip was flipped 90 degrees into the air and reimagined as a vertical structure.

The imposing tower has a tiny footprint compared to the earthbound original, and soars 10 times as high as any of the buildings around it.

But an increase in that order of magnitude is not unheard of, Constable notes.

“When the first skyscrapers were built 100 years ago, they were 10 times the size of the buildings that came before them,” he says. “The Vertical City is not necessarily realistic suggestion. It’s trying to teach us a lesson in scale.”

Given that Vancouver is such a young city, it has the advantage of being able to easily re-invent itself, according to urban designer Scot Hein, one of the founding members of the Urbanarium.

“We didn’t have a 19th century [in Vancouver], so we don’t have the old buildings that cities like Seattle or Portland does, so the fabric here is relatively new,” he says. “In some ways we miss that contextually, because it’s part of the richness of those cities, but in some ways we’re not encumbered by that, as well.”

The vast amounts of overseas investment that has flooded the Vancouver real estate market in recent years has made some owners very rich and provided valuable capital to build infrastructure and amenities, but has also made Vancouver one of the most unaffordable cities to live in on Earth.

“We’re a victim of our own success right now,” says Hein. “We need to think about creatively deploying that capital…to create the Vancouver we want.”

The Way Forward

Whatever path Vancouver takes, it will be decided by its residents, Hein notes.

Given that many Vancouverites weren’t born here and thus have a short memory of how the city came to be, the exhibition also tells the stories of eight instances when the people of Vancouver directly impacted the future of their city.

“People are pretty passionate about this city,” says Hein. “These are seminal moments of advocacy. And that’s important, because it shows people can make a difference, they should have faith hope and courage that they can influence their city.

Arguably the most dramatic instance of citizen-led advocacy was the opposition to the so-called Project 200 that would have seen a large freeway carve its way through East Vancouver and downtown, destroying Chinatown and cleaving the city in two.

“We want people to figure out and become aware about the issues Vancouver faces,” says Dreicer. “We want them to know they can have an impact.”

Throughout Your Future Home, visitors are asked to participate. One exhibit asks you to draw your version of a skyscraper, another asks you describe what the word “home” means to you.

As part of the exhibition, the Museum of Vancouver is also presenting a series of debates and public talks designed to engage the public directly in the conversation.

When it comes to what form the Vancouver of the future will take, Dreicer says it is imperative that Vancouverites use their voice.

“There are many different solutions, and every individual has a chance to take part,” he says. “This is your city.”

The Museum of Vancouver’s newest exhibit, Your Future Home: Creating the New Vancouver is on display until May 15.