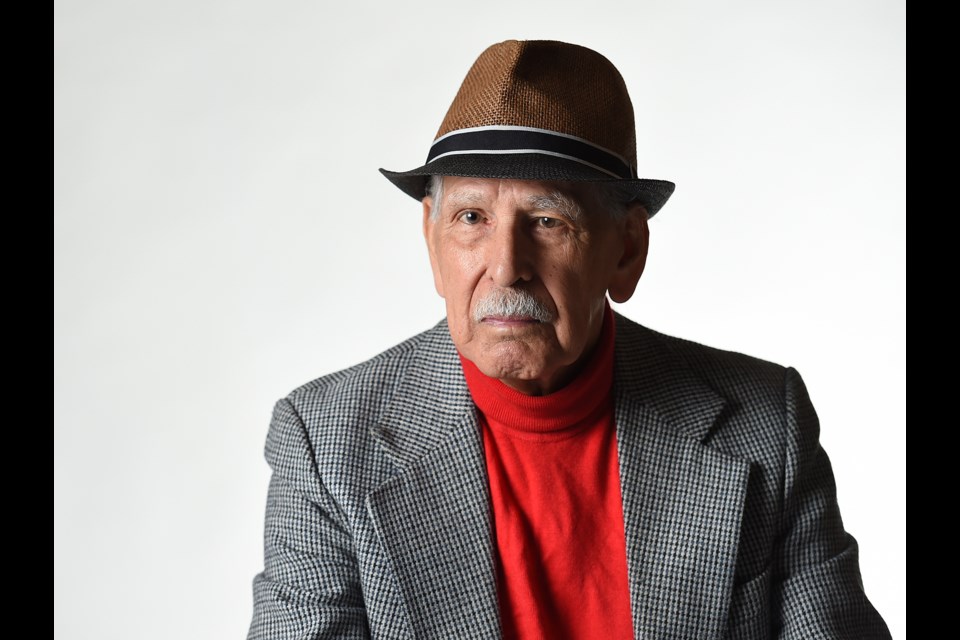

The old “freedom fighter” is gone.

Bill Lightbown, who was a pioneer in the Indigenous rights movement in B.C. and across Canada, died March 1 after complications from a hip injury. He was 91.

Family, friends and many people influenced by Lightbown will gather March 18 at Glenhaven Memorial Chapel on East Hastings to remember the remarkable life of the self-described “freedom fighter,” who leaves behind six children, including his son Shane who is organizing his father’s memorial.

“He was a fighter right to the very end, I’ll tell ya,” said Shane, who is expecting a large crowd Monday. “He didn’t want to go, he wanted to stay. He wanted to finish what he started. He was just one of those people. He didn’t feel like he was finished.”

What he started was a life dedicated to making life better for Indigenous people. That decision was influenced by his treatment as an 18-year-old after an incident in the 1940s in Vancouver that put him in jail.

Lightbown recounted the story three years ago in his apartment, when the Courier interviewed him for a feature story. He was sent to jail for “being an Indian” after a police officer arrested him, his brother and a friend for picking cherries out of a tree at East 14th and Nanaimo.

A judge convicted Lightbown of vagrancy and he served six months in prison.

Upon his release, he was given a letter authored by the solicitor-general of Canada, who wrote that it was “the greatest miscarriage of justice that had come to his attention,” Lightbown said from a chair in his apartment on Frances Street.

“I didn’t know anything about the law, except that I know we didn’t do anything wrong,” he said in October 2016. “Even if we were stealing cherries, I don’t know how that’s a crime.”

That incident propelled the Kootenai First Nation member’s life-long pursuit of justice for Indigenous people. He went on to co-found the United Native Nations Society (originally called the B.C. Association of Non Status Indians) and Vancouver Native Housing Society.

His fighting spirit led him to Gustafsen Lake in 1995, where Indigenous people clashed with the RCMP near 100 Mile House. A good friend of the late William Jones Ignace (also known as Wolverine), Lightbown was a spokesperson for the Ts’peten Defence Committee during the standoff that saw the RCMP fire thousands of rounds of ammunition.

He and his wife, Lavina White, were also at the armed standoff at Kahnawake in Mohawk territory in Quebec. The couple travelled across the country in their advocacy work, including stops in Ottawa where Lightbown participated in a first ministers’ conference related to implementing the 1983 constitutional accord on Aboriginal rights.

Lightbown’s work was largely focused on fighting for the rights of Indigenous people living off-reserve. In that work is where Scott Clark, the executive director of Aboriginal Life in Vancouver Enhancement Society, met Lightbown, whom he described as a mentor.

Clark recalled his time 30 years ago knocking on doors in Surrey to sign up members for the now-defunct United Native Nations Society. Clark worked alongside another young Indigenous activist, Shawn Atleo, who went on to serve as national chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

“Bill took me under his wing and that’s when I first got engaged in Indigenous politics,” said Clark, who is now president of the Northwest Indigenous Council, which is a new provincial advocacy organization for off-reserve people in B.C. that Lightbown co-founded.

He said Lightbown continued to attend meetings and speak about his experience until he died.

“He was one of the very few folks that has been there…who knows the struggle, knows the history, knows the people” Clark said. “So we lost a very valuable person.”

He said he was glad Lightbown lived long enough to learn about two court decisions that favoured the rights of Indigenous people. He pointed to the Daniels decision, which recognized that non-status Indigenous people and Metis people are considered “Indians” under the Constitution.

The other was the Supreme Court of Canada’s landmark decision in 2014 to grant title to more than 1,700 kilometres of land to the Tsilhqot’in First Nation. Coincidentally, Lightbown was reading a newspaper article related to that decision when the Courier visited him in 2016.

The story had to do with the Tsilhqot’in filing a claim in B.C. Supreme Court to “private land” on the same territory the band claimed in their historic Supreme Court of Canada victory. Lightbown had underlined “private land” in red pen.

“That’s bullshit because the reality is, they own the land,” he said. “It’s as if we’re still interlopers and not really sovereign people.”

Lightbown contended the only reason life was getting better for Indigenous people in Canada was because of court decisions and not because of so-called goodwill of governments.

“The government and entities are scared stiff that we’re going to use their own laws against them,” he said at the time. “That’s the reason they’re starting to cooperate with us. For years and years, they didn’t recognize us as people. We are the original people from this land and we deserve the recognition and respect that goes with that.”

Lightbown was born in Golden on April 14, 1927. His mother, Merceline Morigeau, was a member of the Kootenai Nation. His father, David, was a non-native man, who was considered a community leader.

Lightbown left Revelstoke when he was 15. He rode his bike to Vancouver, a journey that took him several days, although he doesn’t remember how many.

He moved in with his sister, enrolled at Britannia high school and landed a job on the docks. Over this lifetime, he would have a variety of jobs, including shipyard worker, fisherman, house painter, car salesman, a logger and a cook.

But it was his fight for the rights of Indigenous people that was his passion.

At the close of his interview with the Courier in 2016, he made a wish.

“Regardless of the fact that this is my land, I want this to be a happy community and I want the people who are living here to be happy with each other. There’s no reason why it should be any other way.”

For more on Lightbown’s life, go here and here.

Lightbown’s memorial service begins Monday, March 18 at 3 p.m. at Glenhaven Memorial Chapel, 1835 East Hastings St. The public is welcome, said his son Shane, who is accepting donations ([email protected]) to help pay for the service of his father, who will be laid to rest in a casket painted in an eagle design.

@Howellings