There was once a time, on any given Friday night, when Warren Isbister would put away his tools and start priming himself for an evening of driving.

The 36-year-old journeyman welder began moonlighting as an UberX driver – or “partner” in the Uber vernacular – in Edmonton soon after the ride-sharing service launched there in December 2014. On a typical weekend, you would find him checking his phone app for trip requests and picking up passengers – on their way to a show, on a date, back home after the bar –into the early hours of the morning.

It was a side job for Isbister, and one that he did for the love of conversation and driving – definitely not for the money. When all his costs – such as gas, taxes, cleaning supplies, snacks for customers, and added wear and tear on his vehicle – and time were factored in, his side gig was barely worth it.

“That’s why Uber has such a high turnover,” says Isbister over the phone from his home in Edmonton. “Basically, people come in, they’re enthused, they realize it’s not so great, and they quit.”

Isbister, like millions of people around the world, was part of what is being called the gig economy or, more broadly, the sharing economy. Facilitated by digital technologies – such as smartphone apps – companies like Airbnb, Upwork, Lyft, Uber and AskforTask, to name a few, have cropped up to offer part-time work opportunities to enterprising, be-your-own-boss-oriented entrepreneurs.

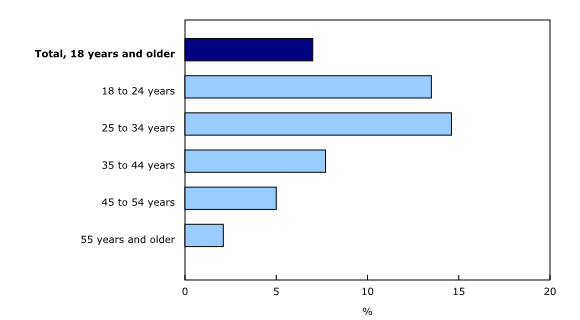

According to Stats Canada, an estimated 2.7 million Canadians aged 18 years and older “participated in the sharing economy” from November 2015 to October 2016, and that’s just counting people using ride sharing services and private accommodation rentals.

Sharing economy organizations are often unregulated or operate in legislative grey areas. However, governments are gradually passing laws in an attempt to get a better deal for local economies and workers.

Vancouver City Council recently voted 7-4 in favour of imposing restrictions on the estimated 6,000 short-term housing rentals operating in the city. Meanwhile, the B.C. NDP is investigating whether or not to allow ride-sharing services like Uber to open up shop.

However, new laws take time to develop. On the whole, says Anil Hira, a professor of political science at Simon Fraser University, “governments are really behind the eight ball when it comes to keeping up with technical regulations.” For example, online transactions, such as those conducted by companies like Amazon, may be made using a different sales tax, giving web-based platforms an unfair advantage over brick-and-mortar storefronts.

On top of that, online gig work opportunities, like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk – a so-called “marketplace” that enables businesses to hire workers to perform tasks that a computer can’t do – can be completed by anyone around the world. This, says Hira, can “lead to potentially major outsourcing of traditional jobs” to workers outside of British Columbia and Canada, a further decline of labour unions, and “residual unemployment – where certain segments of the population just won’t have steady work because of the gig economy.”

The past revisited

The gig economy gained popularity during the recession of the 1980s and 1990s, when North American companies started outsourcing their workforces to reduce costs associated with wages, according to researcher and sociologist Alexandrea Ravenelle.

“Now, it [the gig economy] is a much bigger trend that’s been made cool,” she says. “If it’s a technology company, you’re working off an app, so people don’t question it the same way that they did when companies were laying off their white collar workforce in the ’80s and ’90s.”

Ravenelle, who studied the gig economy in New York for her PhD dissertation, The New Entrepreneur: Worker Experiences in the Sharing Economy, notes that professional downsizers, like disgraced former corporate executive Al “Chainsaw” Dunlap, even made names for themselves by helping companies turn a larger profit through massive layoffs.

Gig economy workers don’t necessarily have a guaranteed number of paid hours, a pension plan, disability insurance or benefits. The result, she says, is a growing number of people who are precariously employed – also called the precariat – people who work long hours for little pay and live with a great deal of uncertainty.

The reality we’re faced with now, she says, is that the profits being made by the sharing economy often come at a cost to workers. “We are moving back into almost a pre- or early-industrial era when it comes to workers’ rights and protections,” she says.

Why many of us are along for the ride

Isbister says he sees the upsides and downsides of his former part-time gig. On the plus side, he appreciates the quality of service Uber offers to its customers in terms of the availability and cost of rides.

“Most people said that their ride was anywhere from 40 to 80 per cent cheaper than a cab,” he recalls from his experience, “and typically drivers would respond in anywhere from one to 10 minutes. On the other hand, people would tell me stories where they had to wait 30 minutes to two hours for a cab.”

Drivers also have an opportunity to make money, but likely as a side gig on top of one or more other jobs.

“The only people that maybe have some repercussions are the [Uber] drivers,” he says. “It would be nice if they could take more of a cut of the fare.”

Indeed, Uber drivers have recently been demanding better wages and working conditions, with protests staged in New York and San Francisco last year over wage cuts. But the fact is that Uber can offer its customers lower fares because it doesn’t pay its drivers a guaranteed salary, require certain permits (unless mandated), or lease vehicles to drivers, as is often the case with taxi companies.

What’s worrying about the growth of the gig/sharing economy, say experts, is the impact it’s having on the number of full-time jobs now and into the future.

Already, between 2006 and October 2017, the number of self-employed British Columbians grew by around 43 per cent, according to Statistics Canada figures, while the number of employees in B.C. grew by less than eight per cent. Over that same time period, part-time work in B.C. increased by almost 19 per cent and full-time work by about 14 per cent.

For the sake of protecting the rights and financial security of workers, Ravenelle notes, there is an urgent need for governments to step in and regulate.

“The default categorization for workers should be ‘employee,’” she says, to ensure part-time workers will still qualify for benefits, workers compensation and other workplace protections afforded to full-time employees.

“Research shows that there are companies in the sharing economy that have categorized their workers as employees and they are succeeding,” such as housecleaning company MyClean, she says. These companies find success because of lower worker and customer turnover, as workers tend to be better trained and happier with their employment situation overall.

“The problematic aspect for some sectors is that it [the gig economy] is global in scope,” says Hira. “So, at the local level, for companies like Uber, you need to have sensible regulations, but for the [larger] gig economy, you need a global set of regulations, and that, of course, is going to be a much more evolutionary process.”

Meanwhile, a steady stream of new companies – like Vancouver’s own Quupe online product rental/lending platform – are coming onto the market to compete with traditional businesses, such as equipment rental storefronts.

For Isbister, it’s a matter of choice. If people want to participate in the gig economy as Uber drivers, he says, governments shouldn’t stand in their way.

“I think Vancouver should welcome a service like Uber,” he says. “It’s up to every driver to figure out their situation and if it’s worth their while.”