A specialized educational program at Simon Fraser University that helped dozens of aboriginal students pursue a post-secondary degrees was cut suddenly last week, a move faculty said contrasts with the university’s decision to put $9 million into reconciliation efforts.

Natalie Knight, an instructor with the Aboriginal University Transition Program that first launched at SFU in 2011, said she and the program’s director were informed April 19 that the education initiative was immediately cancelled despite funding they believed endured until the end of the 2017-18 academic year.

“It’s been clear the program was funded through 2018,” said Knight, a member of the Yurok and Navajo nations who is also completing her PhD at SFU in First Nations literature.

In an email through the university’s communications team, the vice-president of academics, Peter Keller, said AUTP, which is known as a pathway, bridge or transitional educational program, was not succeeding in part because it did not draw enough students who could develop the skills and knowledge needed for university entrance.

“The current program had a pattern of declining enrolment and a challenge finding applicants prepared well enough so that we don’t set them up for failure, either within the transition program, or once they embark on regular undergraduate studies at SFU,” said Keller. “Despite considerable efforts, we had only a very few applicants again for the next cohort [in 2017-18], with most not meeting qualification requirements. The program therefore is not meeting its goals and has become unsustainable.”

Annual funding was nearly $300,000. Tuition was roughly $3,000 a semester.

A spokeswoman for the university said “SFU is deeply committed to increasing indigenous student enrolment and to offering an enhanced bridging program to meet this goal. Building successful pathways for indigenous students is a priority for the university and SFU's Aboriginal Reconciliation Council.”

Student status

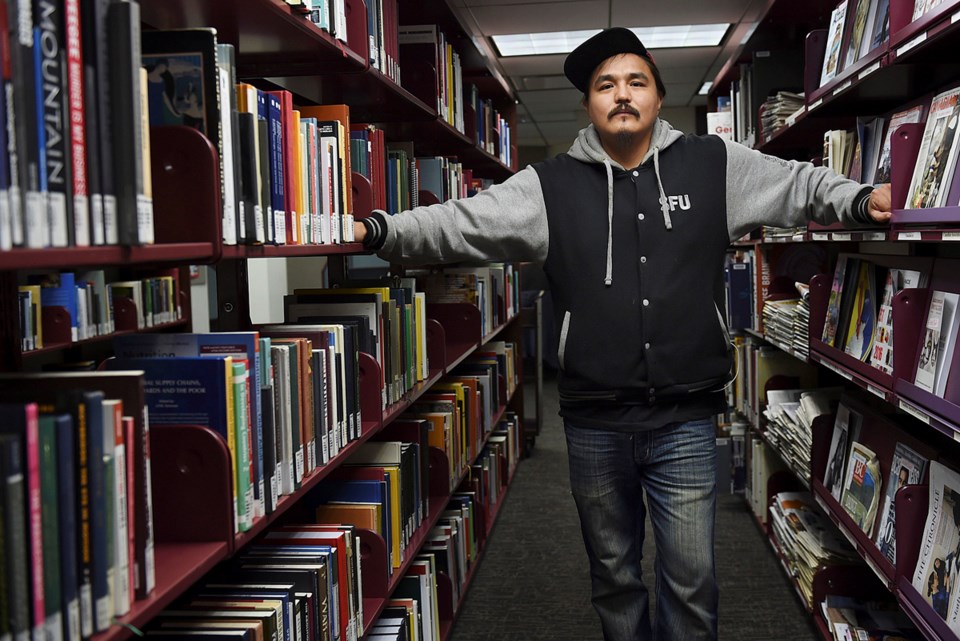

Herb Varley criticised the decision, saying it contradicted the spirit of reconciliation and is a major misstep by the university.

The writer and political activist will start the first semester of his undergraduate degree at SFU since he recently completed the pathway program.

“I’ve been out of school for 14 years,” said the 33-year old Mowachaht student who grew up in Vancouver, attended Britannia secondary and now lives in the Downtown Eastside. “I didn’t have the grades I needed to get into a university, so this was my only opportunity. I am an autodidact, but this was about trying to learn how to be a student and not just a learner. We learned how to write in an academic language, mechanical reasons to the formatting, methods of note taking and knowledge retention, and a class dedicated to learning strategies.”

He said academia is not welcoming to the majority of indigenous learners. His mother attended residential school, and Varley never finished high school.

“A lot of people are leery about attending any type of post-secondary because of the legacy of colonialism and the residential school system,” he said. “The cutting of this program is so messed up, especially in the context of Canada 150.”

He said “there will be a lot of talk about reconciliation” with “welcoming totem poles and renaming places,” but that symbolism does nothing for the ongoing support of the indigenous education pathway program he values.

“Canada has set this program up to fail, but it was the strength of the students and faculty that made it work. The program has been working,” said Varley, pointing out indigenous students once sacrificed their formal aboriginal status under Canadian law if they graduated from university because of stipulations in the assimilationist Indian Act.

(Status could be denied for numerous reasons, including for people who enlisted in the army or joined a professional guild, and for women who married a man without status.)

Numbers game

The university released the enrolment rates to the Courier but did not include the number of students who completed the program nor how many realized the goal of the transitional program by advancing to post-secondary study at SFU or elsewhere. In six years, a total of 70 students enrolled in AUTP.

When it launched in the 2011-12 academic year, 10 students enrolled in the general prep program, specifically known as the AUPP. In three of the following four years, nine students enrolled, but this most recent year, that number dropped to five. In a parallel pre-health bridge program for entering health sciences education, the enrolment was above nine for the first three years until two years ago when it dropped to only two students, who were subsequently integrated with the larger cohort in general studies. After that, the pre-health program was cancelled.

The two pathway programs drew aboriginal learners from across the country and each was capped at 12 students.

Knight disputed that only five students enrolled in the program for 2016-17. “Their number is just wrong. We had nine students in total,” she said.

In the general prep program, the AUPP, she said seven students were new this year while two were returning from the previous year for further study. She could not explain the university’s different account for class size.

“In my perspective, I think they have an error in their counting. I have my roster in front of me and I have double-checked. I have counted my students, and there are definitely nine names there,” said Knight.

A pathway to SFU?

Keller said a replacement will take over for the cancelled indigenous university transition program.

“It is my responsibility to ensure that programming achieves its objectives, and that we don't admit students into programs whose continued existence can no longer be sustained, or that risks setting students up for possible failure. We therefore reached this difficult decision while remaining firmly committed to seeking alternative bridges and pathways for indigenous students to access post-secondary education at SFU.”

He said the university will move in a different direction that involves indigenous input to “participate in redesign of the program to be more attractive to and better meet the needs of indigenous students” and also aligns with the university’s Aboriginal Reconciliation Council, a well-funded but short-term initiative that grew from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

A new committee will form, and Keller will appoint a chairperson and members to establish a new pathway program.

“I will hold the group accountable to present a re-envisioned program built collaboratively by SFU and aboriginal communities with reporting back aiming for the end of 2017,” he said.

Knight did not know how many students have advanced to college or university programs after completing the AUTP at SFU, but said the program’s objectives are not to funnel students exclusively to SFU. She said numerous grads pursued education at Douglas College because it offered a desired course not available at the university, and also referred to a Mohawk man who returned east for further education and a woman who pursued midwifery.

“It’s been indicated to me that the way they are measuring success is based on students that finish and enrol at SFU. If that is how they are measuring success, they are not getting it,” said Knight. “The whole point is to give students the skills to go to university or go on to higher-education.”

Knight said SFU did not do enough to promote the program, which she said explains the sharp drop off in enrolment.

“I am disappointed they did not consult with us,” she said. “We could have worked together on a revised program.”

In regards to consulting the Aboriginal Reconciliation Council, known as ARC, Knight does not know why the program’s participants, instructors and director were not invited to contribute feedback and ideas before being informed of the cuts.

The $9 million invested into ARC must be spent in three years, a fact that Knight said makes her doubt the lasting future of a pathway program. She said she will be attending public ARC meetings and will be launching a petition to reinstate the existing program.