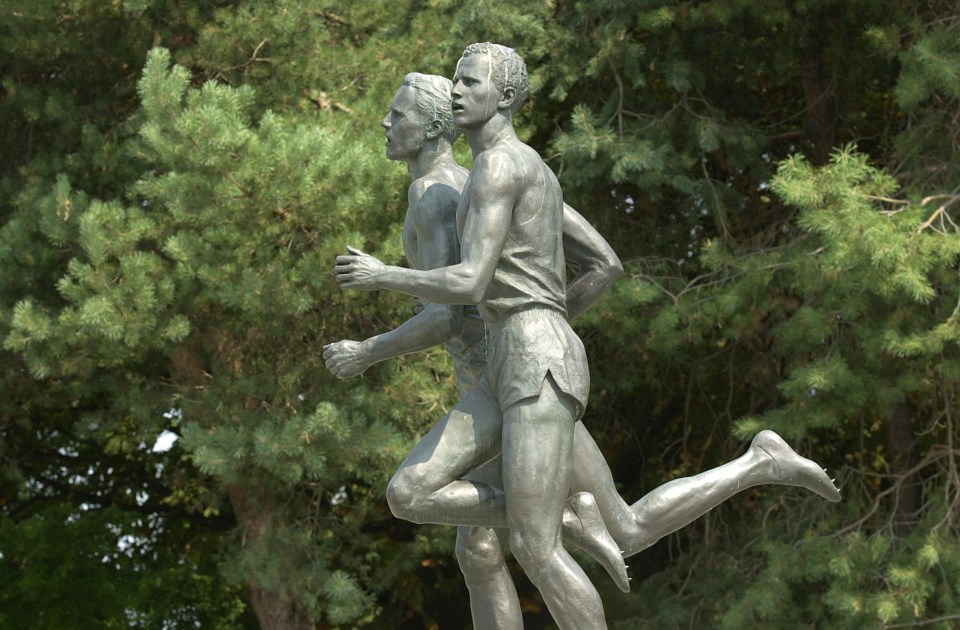

When I was kid, my parents would take me to the PNE once a summer. Before we entered, my dad would be sure to stop at the entrance of Empire Stadium to look up at the statue of two towering bronzed runners frozen in time. I’d ask my dad to tell me, one more time, the story of those two men.

“That’s Roger Bannister and John Landy. They ran the Miracle Mile right here in Vancouver a long time ago,” he’d explain. “You see how Landy is turning his head ever so slightly to the left? That’s the moment when Bannister passed him on the right to win the race. And the whole world was watching.”

The split-second drama of the story has always captivated me, just as it has for generations of sports fans.

Before Expo 86, before the Summer of Love, before the Beatles and Elvis Presley, it was the Miracle Mile that put our sleepy logging outpost on the international map. The race occurred on Aug. 7, 1954, in the newly constructed Empire Stadium in Hastings Park.

It was a scorching hot sunny day, the way our days in early August can be. The North Shore mountains loomed large in the background to provide a spectacular backdrop for the more than 35,000 fans who filled the stadium and surrounding grounds. The race was the big-ticket event on the final day of the British Empire and Commonwealth Games, during what is now considered the Golden Age of track and field.

Three months earlier, on May 6, 1954, in Oxford, England, Bannister had captured the hearts of the Commonwealth and the world when he became the first athlete to run a mile in under four minutes — a feat thought impossible for a human being. The war had been over for almost a decade, but England was still under strict austerity measures while London slowly rebuilt itself from the rubble.

When Bannister crossed the finish line in Oxford, his time was announced to a pin-drop silent crowd. The only number the Brits needed to hear was “three” before they broke into wild cheering. The feat made Bannister a global hero and finally gave the Commonwealth a moment to truly celebrate since the Second World War victory party.

Months later in Vancouver, anticipation for the “The Mile of the Century” was at a sweaty, fever pitch. Unlike in England, when Bannister was racing himself and the clock, this time he’d face the clock and seven other runners from around the Commonwealth. It should be noted that all the racers were white men, an unfortunate representation of the white-first, man-first, British Empirical society of the time, the ramifications of which we are still coming to terms with to this day.

Bannister’s most formidable opponent was Australia’s John Landy, and thirst for the race was so great that CBC TV managed one of its first-ever national broadcasts. While millions watched on TV, an estimated 100 million worldwide listened to the Vancouver event on the radio.

When the starting pistol fired into the blue summer sky, a New Zealander took the early lead, but was quickly overtaken by Landy, who led for most of the mile. Bannister soon moved into second. Then, the Moment: Hearing or sensing Bannister on his tail, Landy glanced over his left shoulder. In an incredible last stretch burst of speed that sent the crowd into hysteria, Bannister passed Landy on the right and crossed the finish line victorious, collapsing into the arms of Mounties in full uniform.

It was Bannister’s best running time ever at 3:58.8, while Landy clocked in at 3:59.6. It marked the first time in world history that two men had broken the four-minute mile. The race became one of the defining moments of sports history in the 20th century.

In 1967, to celebrate Canada’s centennial, Vancouver sculptor Jack Harman was commissioned to create the bronze statue that stood in front of Empire Stadium until the stadium was torn down in the early 1990s.

The statue was saved, and relocated to the corner of Renfrew and Hastings for 20 years. In 2015, it was moved to the north side of the new Empire Fields, with the massive North Shore mountains looming in the background, exactly where the feat took place 64 years ago.

Earlier this month, Sir Roger Bannister died at age 88 at his home in Oxford, England. And while his record has since been beaten several times and is currently held by Hicham El Guerrouj of Morocco, Bannister will live on forever as the man who ran the Miracle Mile, and the man who put this little coastal outpost on the map. And I’ll be sure to pass on the story to my son the next time we stop in front of that statue in Hastings Park.