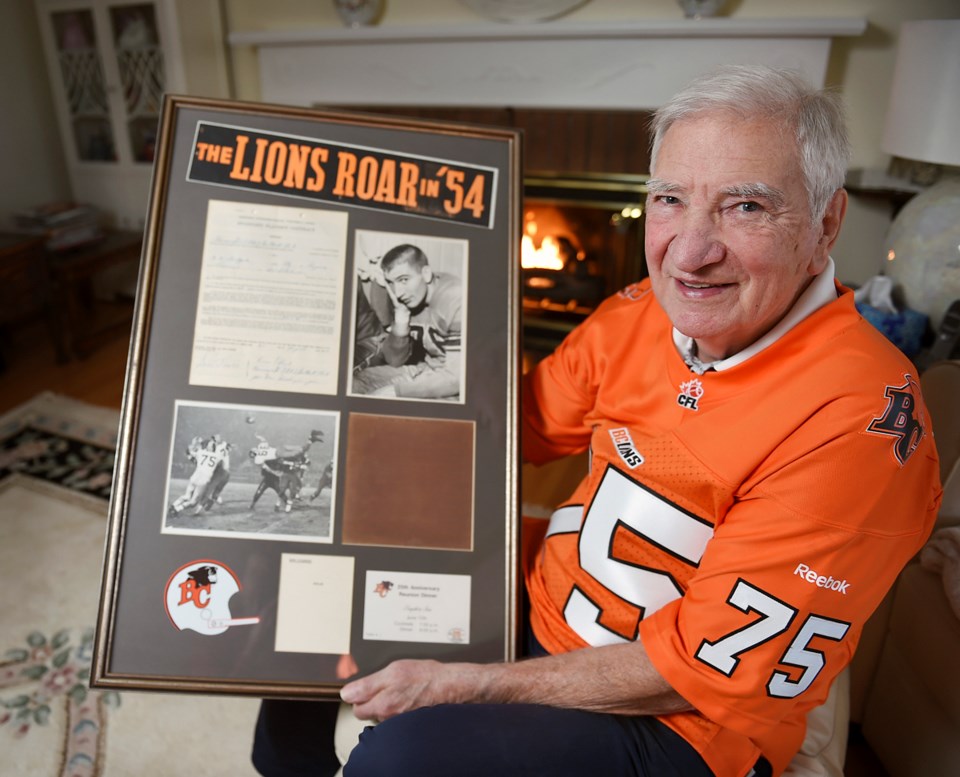

At six-foot-two and 205 pounds, one of the toughest linebackers in Vancouver’s football history answered to the improbable nickname of “Mouse.”

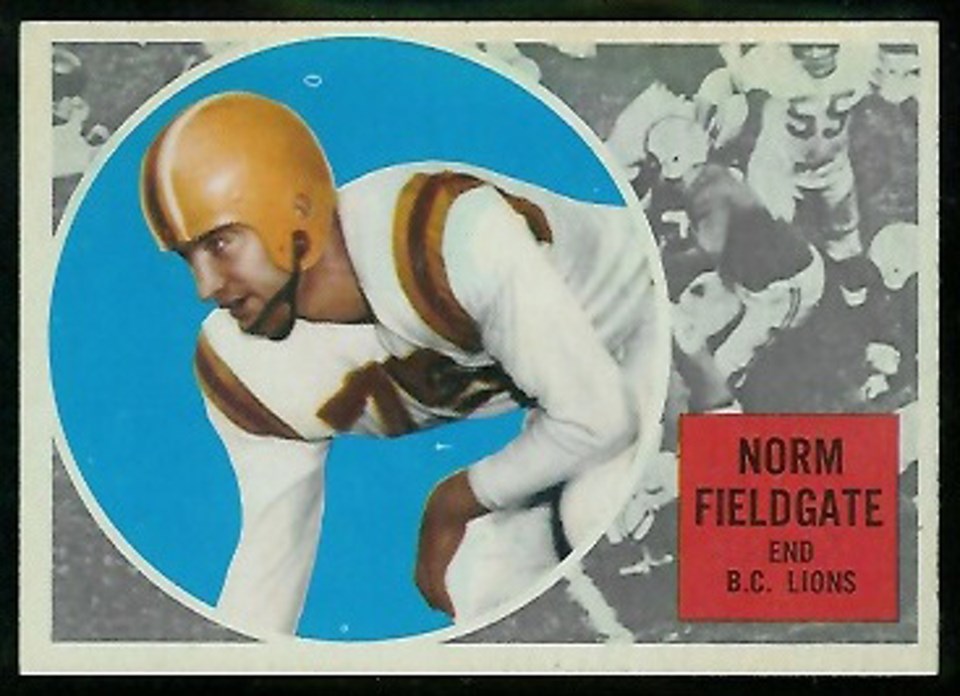

“When I was a kid in Regina I was just a little guy, and they called me Mouse,” said Norm Fieldgate, who was 22 when he became the first player signed to the B.C. Lions.

“When I came to Vancouver to play football, nobody knew that. But soon a few of my buddies came out and they called me that again.”

Hunting his half-back prey off the line of scrimmage got Fieldgate named to the 1959, 1960 and 1963 Western All-Star teams and to the CFL All-Star team in 1963. The next year, he won the Grey Cup with B.C., dropping Hamilton 34-24 in Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium by holding off a come-back from the Tiger-Cats who had defeated the Lions a year earlier.

From the 1954 expansion season through two Grey Cup games until his final season of 1967, Fieldgate played 223 games in 14 years with B.C. The Lions retired his sweater, No. 75, soon after the player hung up his cleats.

Now 83 and living in North Vancouver with his wife Doreen, Fieldgate said the Lions’ 1-15 record was so dismal their debut season, the team’s lone win called for champagne.

“We weren’t really a great team but we did manage to win one game that year so we had quite a celebration,” he told the Courier, explaining that the whole team — minus head coach Annis Stukis — partied late into the night at a Vancouver hotel, even though most had regular jobs in the morning.

That first win, on Sept. 18, 1954 was a great milestone. When the Western Interprovincial Football Union (a precursor to the CFL) finally agreed to add a fifth team to its professional league in Feb. 1953 (and after much lobbying by team president Art Mercer, vice-president Bill Morgan, treasurer Bill Ralston, and secretary Ned Wiginton) the one thing Vancouver needed most for that bid — a new stadium — didn’t exist. But the pieces were already within their grasp.

Two years earlier Fred Hume, Vancouver’s mayor from 1951 to 1958, had pushed for a permanent stadium for the upcoming British Empire Games, and a city plebiscite had approved spending $750,000 although it eventually cost twice that much. A city bandwagon of support even approved the bulldozing of Hastings Golf Course to make way for the new Empire Stadium at Hastings Park.

After funding compromises left the stadium with fewer seats and only one-third of its stands covered, it was nonetheless finished in time for the Empire Games. It held 25,000 seats and room for 7,000 more standing spectators, giving the West a leading venue for Grey Cup games. (Dominion championships were almost exclusively held in eastern venues such as Toronto’s Varsity Stadium, holding 27,500 fans.)

When Roger Bannister out-stepped John Landy in the last lap of the famous Miracle Mile at the Games on Aug. 7, the Lions stood anxiously by waiting to practice for their first pre-season game four days later.

Waiting with them was Stukis, who’d been pried from the Edmonton Eskimos. Stukis had shrewdly enticed NFL players who lived in Washington State to sign with B.C. and he offered them equal or better pay to that of the NFL. This triggered outrage and even legal threats from teams in Washington, New York and Philadelphia Eagles, especially when the Giants’ captain, Arnie Weinmeister, turned his back on the NFL to reportedly earn $25,000 to play tackle for B.C.

Another renegade from the NFL was fullback Byron Bailey, formerly of the Green Bay Packers, who became a B.C. hero. Bailey scored the Lions’ first touchdown and 28 more in his 11-year career. He led the Lions in rushing three times and made the Western Division’s all-star team in 1957.

But Fieldgate was the first player Stukis signed. A native of Regina who shuttled between Saskatchewan and Vancouver, Fieldgate had made every amateur team he had tried for — the Regina Rams (of the Canadian Junior Football League), UBC Varsity (in the U.S.-based Evergreen Conference), and the Vancouver Cubs (of theBritish Columbia Intermediate football League, set up as a farm league by the B.C. Lions).

During an especially rain-soaked autumn in 1954, field conditions factored in many games.

“The field got chopped up pretty good,” said Fieldgate. “We had some pretty mucky, muddy games. I was playing defense and I was pleased because it brought those fast guys down to my speed.”

As a rookie that year, he made $2,000 for the season, and the Lions helped him find a job at Burrard Dry Dock in North Vancouver. He worked almost simultaneously, toughing it out on the port and the gridiron. When his shift finished, he drove his new ’54 Pontiac across the original Second Narrows Bridge to Empire Stadium for football practice.

“It was a long day,” said Fieldgate.

Practices typically lasted an hour, and football technique differed a lot from today. Players filled many roles and they all practiced offense and defense.

“You always had a back-up for every position,” said the linebacker. “A lot of times I went in as the offensive end and caught a few passes.”

The running game ruled the CFL in those days. When players converged at the line, the snap came instantly to prevent the defense from gleaning any of the offensive strategy. The two teams would close together like Viking shield walls, and Fieldgate acted largely on instinct.

“Most of the plays, you had to chase the guy down,” he said. “If there was a pass behind you, you had to chase him and bring him down. But it was a team game, so there was never any individual that did anything all on his own.”

Fieldgate had a system to deal with faster half-backs.

“I didn’t really have that much speed, but we chased them down eventually. They would zig-zag, but we compensated for that — you always made sure you had a speedy guy behind you so when [the runner]got behind you, you picked himup.”

The Lions’ nine-year rise to back-to-back Grey Cup finals in 1963 and 1964 hinged on players sticking around, said Fieldgate.

“Finally the Lions were able to get enough players that were with the team long enough for cohesion. By Bailey stayed. Joe Kapp stayed. Willie Fleming stayed. Because individuals weren’t much good to you unless you had them working together.”

The wet field conditions in Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium in 1964 might have helped Fieldgate and the Lions feel at home in their Grey Cup win over the Hamilton Tiger-Cats. As for the long decline after the Lions’ victory in 1964, Fieldgate said, “It’s a fine line between winning and losing in most cases. Sometimes we’d get the hell beat out of us. But other times the games were fairly close. A touchdown here, a knocked-down pass there. It was very competitive.”

Current Lions teams can relate to that.

Fieldgate finished his career with 62 turnovers, 37 interceptions, two of them returned for touchdowns and 25 fumble recoveries.(No stats were kept for tackles or sacks.) He hung up his cleats after the 1967 season at the age of 36.